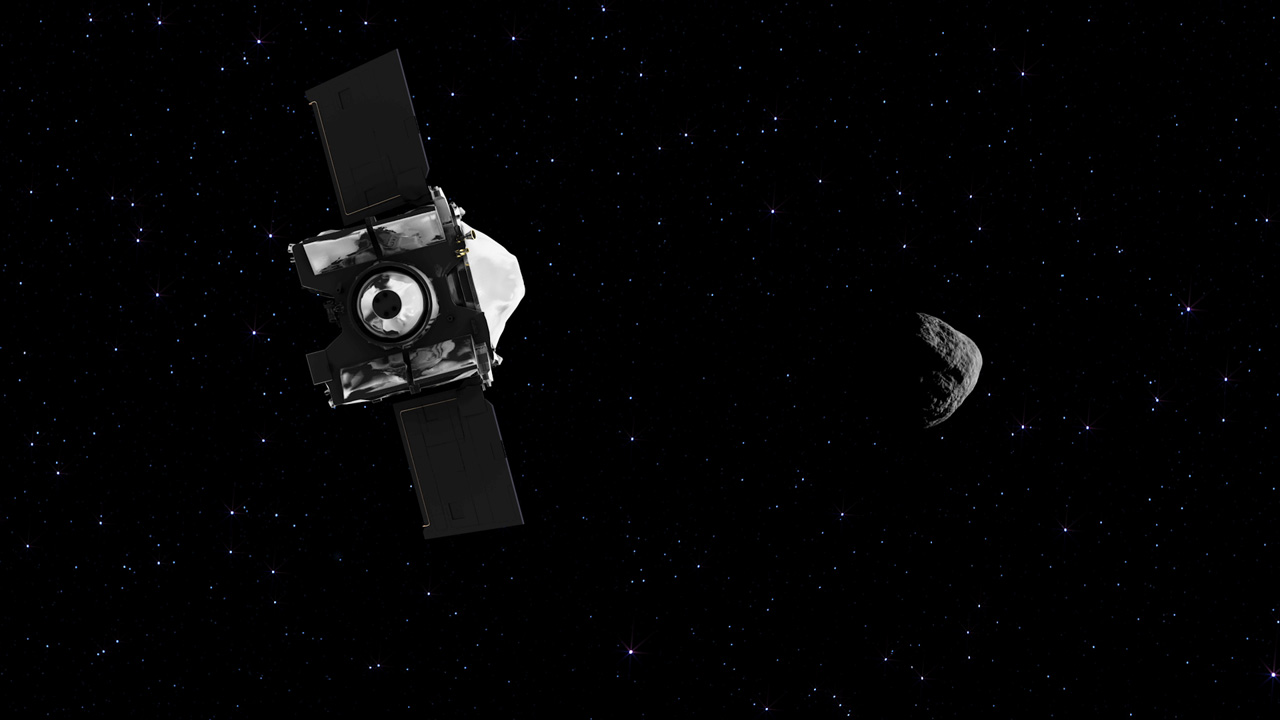

Featuring image: Artists impression of Hayabusa2 approaching Ryugu. Image credit: NASA/JPL, Public Domain (CC0)

Paper: Uracil in the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu

Authors: Y. Oba, T. Koga, Y. Takano, N. O. Ogawa, N. Ohkouchi, K. Sasaki, H. Sato, D. P. Glavin, J. P. Dworkin, H. Naraoka, S. Tachibana, H. Yurimoto, T. Nakamura, T. Noguchi, R. Okazaki, H. Yabuta, K. Sakamoto, T. Yada, M. Nishimura, A. Nakato, A. Miyazaki, K. Yogata, M. Abe, T. Okada, T. Usui, M. Yoshikawa, T. Saiki, S. Tanaka, F. Terui, S. Nakazawa, S. Watanabe, Y. Tsuda and Hayabusa2-initial-analysis SOM team

Bringing a space probe to an asteroid is hard. Bringing back a piece of that asteroid to Earth is even harder. Nevertheless, Hayabusa2 successfully brought back samples from the asteroid Ryugu and gives us valuable insight on the abundance of biomolecules in our solar system.

What the Japanese space agency JAXA accomplished is extraordinary. After the successful sample return mission of Hayabusa from asteroid 25143 Itokawa in 2010, the successor mission again was able to bring us back precious, pristine asteroid material, including gas samples. In contrast to Itokawa, the new target Ryugu represents a much more pristine asteroid, chemically connected to a class of meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites. Researchers already detected the very building blocks of life, like amino acids and nucleobases, in these meteorites. The careful analysis of the Hayabusa2 samples revealed that one of the nucleobases, uracil, is also present in Ryugu.

Continue reading “Biomolecules on icy worlds”