Thawing permafrost is known to be a substantial source of greenhouse gases to our atmosphere, yet scientists may still be underestimating this frozen giant. Permafrost soils store twice the amount of carbon than is currently in the atmosphere, but icy temperatures prevent microbes from converting carbon in the soil to greenhouse gasses. This creates a sort of carbon lockbox in the arctic. However, as climate change warms our planet, this once-frozen carbon threatens to escape to the atmosphere as the potent greenhouse gas, methane. A new study by Dr. Katey Walter Anthony and colleagues changes the paradigm of permafrost science and warns that current models underestimate the amount of methane that permafrost thaw in regions of Alaska and Siberia could release.

Continue reading “Permafrost Paradigm Shift Suggests More Methane Emissions to Come”Metal-Eating Microbes Who Breathe Methane

Featured Image: Murky pond in Alaska with “rusty” iron-filled sediments. Image courtesy Jessica Buser. Used with permission.

Authors: Alina Mostovaya, Michael Wind-Hansen, Paul Rousteau, Laura A. Bristow, Bo Thamdrup

The table has been set and the food is all prepared. But this is no ordinary dinner party, it’s a microbe party! The guests sit down and proceed to dig into the main course; sulfur, rusty iron, and methane. Curiously, the guests are feeding each other, not themselves! This image seems pretty weird to us humans, but it’s a delight to these microbes. This collaborative method of eating occurs in pond and lake mud all around the world. In a new study, Mostovaya and colleagues describe one such feast in Danish Lake Ørn, that is not only collaborative but may mitigate climate change.

Continue reading “Metal-Eating Microbes Who Breathe Methane”Prehistoric Microbial Meals Found in the Australian Outback

Featured Image: Rock fracture from the Dresser Formation, Australia. Fluid inclusions are trapped in the white stripes. Image courtesy Ser Amantio di Nicolao, used with permission.

Paper: Ingredients for microbial life preserved in 3.5 billion-year-old fluid inclusions

Authors: Helge Mißbach, Jan-Peter Duda, Alfons M. van den Kerkhof, Volker Lüders, Andreas Pack, Joachim Reitner, Volker Thiel

Just a few weeks ago NASA made a historic landing of the Perseverance rover on Mars. This rover symbolizes our human drive for exploration and the need to find the origins of life to answer the big question—are we alone in the universe? In addition to extraterrestrial investigation and research, we can address this fundamental question here on our own planet by digging into extreme environments that are analogs for ancient Earth or other planets. These unusual environments, such as hydrothermal vents in our deepest oceans, boiling hot springs in Yellowstone, and prehistoric lakes in South America, can give us glimpses of ancient information and clues about to the ingredients of life. By discovering our own origins of life, we can begin to understand how it may evolve on other planets.

Continue reading “Prehistoric Microbial Meals Found in the Australian Outback”Hunting for Antibiotics in Caves

Featured Image courtesy Doronenko and Wikimedia Commons

Paper: High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis of the Actinobacterial Spatial Diversity in Moonmilk Deposits.

Authors: Marta Maciejewska , Magdalena Całusińska, Luc Cornet, Delphine Adam, Igor S. Pessi, Sandrine Malchair, Philippe Delfosse, Denis Baurain, Hazel A. Barton, Monique Carnol and Sébastien Rigali

Do you ever think about the microbes around you when you go caving? Me neither, but a team of scientists from Belgium did.

Actinobacteria are found in many places around the world, including volcanic terrains and ice caves. They are of particular importance to cave ecosystems and structure since the formation of speleothems (cave formations) like moon milk is thought to be aided by Actinobacteria. These microbes are known for their ability to produce filaments and aid calcium carbonate deposition and precipitation, which could be important for the mineral deposition that forms speleothems.

Despite the importance of microbes in caves, our understanding of microbial communities and spatial distribution within a cave is still fairly limited, i.e. we still don’t know which microbes dominate cave formations and where they live. An international team of scientists set out to answer these questions using three speleothems in the Grotte des Collemboles (English: Springtails’ Cave) in Belgium. Using sterile scalpels, the team scraped soft moonmilk deposits from the walls of the cave into tubes to understand whether different speleothems in the same cave have different bacterial communities.

Using high-throughput DNA sequencing, they found that all the moonmilk deposits had over 700 species in common but distinct communities of bacteria. At least 10% of the species on a particular speleothem were unique to it, and they identified over 4,000 species in total. Actinobacteria was the second-most abundant group (after Proteobacteria) across deposits and many Actinobacterial groups like Nocardia, Pseudonocardia and Streptomyces were found at every speleothem.

Within Actinobacteria, the genus Streptomyces showed the highest diversity (19 species) across all sites even though they only comprised 3% of the actinobacterial community. Interestingly, the team could only grow 5 of these Streptomyces in the lab, which reinforces the significant obstacles to culturing microorganisms still faced by microbiologists.

Streptomyces are already a prodigious source of antibiotics and other biologically important compounds, but could these speleothem communities be a source of novel antibiotic compounds? The answer might be worth exploring, given the diversity of Streptomyces found in just this one cave but also the emerging roles of other Actinobacteria in antibiotic production.

The difficulty of growing in situ the bacteria we find in cave formations might complicate our ability to study the compounds they produce, but such adventures could still offer fascinating insights into the microbial inhabitants of caves and how they help bind mineral formations together. The next time you go caving, hopefully you’ll think about the Actinobacteria that surround you!

Hunting for Antibiotics in Caves by Janani Hariharan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Mosaics of Life Along a River

Featured Image: Small headwater stream in Oregon’s Mountains. Image courtesy Jessica Buser-Young, used with permission.

Paper: The River Continuum Concept

Authors: Robin L. Vannote, G. Wayne Minshall, Kenneth W. Cummins, James R. Sedell, Colbert E. Cushing

Perhaps last time you went for a hike, you stumbled upon a burbling spring pushing its way up through the leaf litter after a heavy rainfall, creating a tiny rivulet of water crisscrossing over your path before plunging back into the forest. What a find! Excitedly, you squatted down and gently uncovered the spring to notice gnats lazily floating away, some nearby fruiting mushrooms, and great clumps of decomposing twigs and leaves which you assume harbor uncountable numbers of microorganisms. This unique little ecosystem is profiting from the nutrients and water being pushed from the ground, using the opportunity to have a feast. But what happens to the nutrients and carbon that gets past these plants and animals?

Continue reading “Mosaics of Life Along a River”New instrument maps and preserves frozen habitats on Earth- and potentially icy worlds

Featured Image: Iceberg in North Star Bay, Greenland by Jeremy Harbeck – NASA, Public Domain

Authors: Michael J. Malaska, Rohit Bhartia, Kenneth S. Manatt, John C. Priscu, William J. Abbey, Boleslaw Mellerowicz, Joseph Palmowski, Gale L. Paulsen, Kris Zacny, Evan J. Eshelman, and Juliana D’Andrilli

Like the rings of a tree, core samples extracted from glacial ice preserve a unique record of past events. But instead of recording seasonal growth, the ancient ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland have preserved the conditions of long gone climates and ecosystems. Some sheets have continuously accumulated so much snowfall over the past series of millennia that in some places the ice can reach depths that are miles deep. Analyzing this immense glacial record can inform us about not just the global patterns of climate change, but also the evolution of microbial life on Earth, and maybe even the icy worlds of our Solar System.

Continue reading “New instrument maps and preserves frozen habitats on Earth- and potentially icy worlds”Do Microbes Release Fluorine from Rocks?

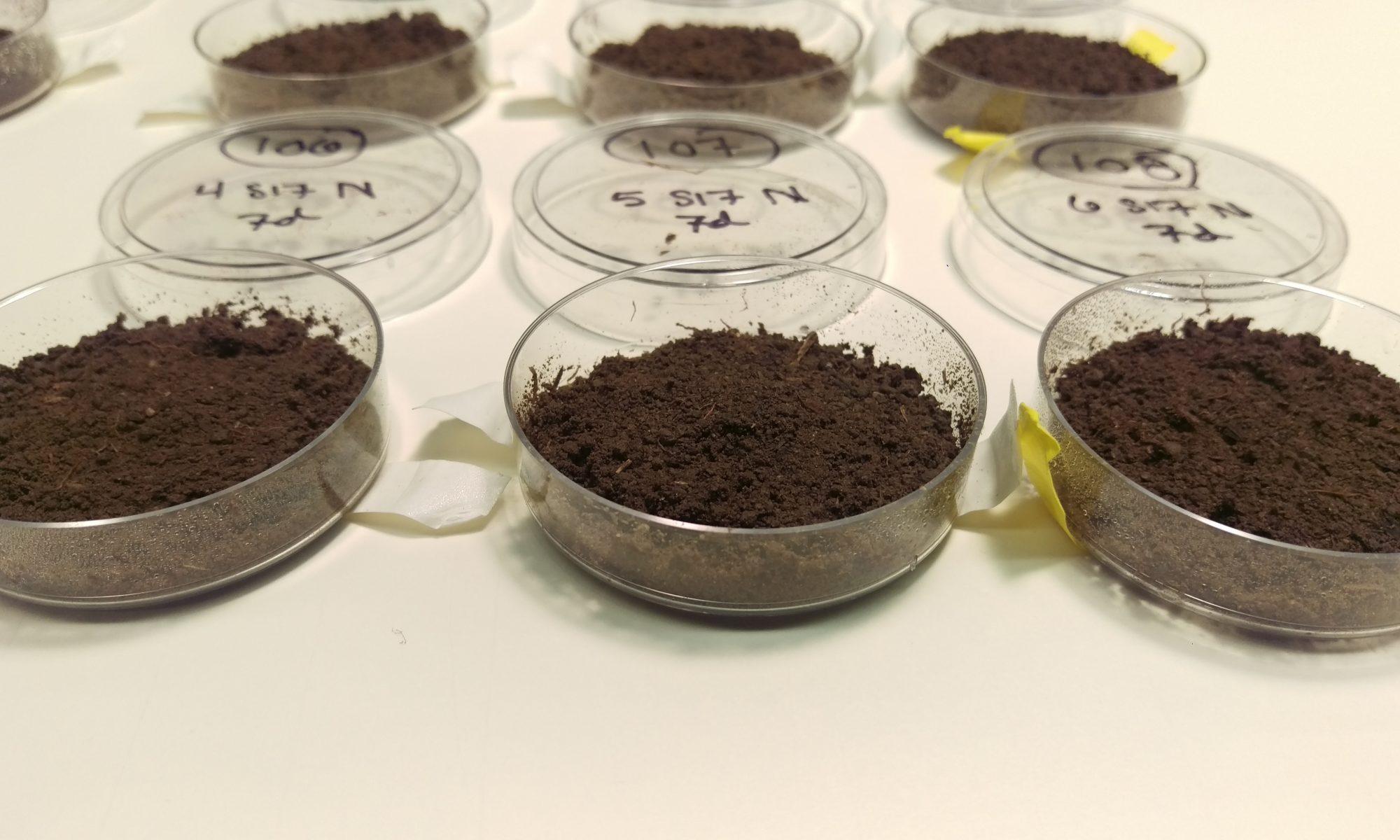

Featured Image used with permission of photographer (Cassi Wattenburger)

Paper: Indigenous microbes induced fluoride release from aquifer sediments

Authors: Xubo Gao, Wenting Luo, Xuesong Luo, Chengcheng Li, Xin Zhang, Yanxin Wang

My science textbook taught me that fluorine (F) was really important for dental health, and I’ve since learned that both excessive and insufficient amounts of fluoride in groundwater can cause health issues. While the chemistry behind the release of fluoride ions from rocks or sediments into groundwater is well understood, the microbiology of this process is not. Specifically, scientists have been wondering whether microbes could speed up the release of F from sediments into groundwater.

Continue reading “Do Microbes Release Fluorine from Rocks?”Ancient microbes engineered sedimentary deposits

Featured image: Cambrian stromatolites from New York State. Image attribution: James St. John / CC BY 2.0; Wikimedia Commons

Paper: Evidence for microbes in early Neoproterozoic stromatolites

Authors: Zhongwu Lan, Shujing Zhang, Maurice Tucker, Zhensheng Li, Zhuoya Zhao

Stromatolites are ancient, layered deposits of sediments that are characterized by thin, alternating light and dark bands. While microbial fossils have been found in many stromatolites, the biological origin of these structures has been debated. Continue reading “Ancient microbes engineered sedimentary deposits”