Featured Image: Artist’s impression of ESA’s ExoMars rover ‘Rosalind Franklin’ on the surface of Mars. Credit: ESA.

Authors: Quantin-Nataf et al., 2021

We are entering a new dawn of Mars exploration: Perseverance rover touched down on Mars earlier this year, which marks the start of what will be a decade-long effort to return samples from Mars. In 2022 the European Space Agency (ESA) will launch the ExoMars rover, which will team up with the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) to find evidence of past or present life on Mars.

ESA’s new rover is set to touchdown on the red planet in 2023. Named Rosalind Franklin – after the prominent scientist who contributed to the discovery of the structure of DNA – the rover aims to search for signs of past or present life on Mars in an area called Oxia Planum.

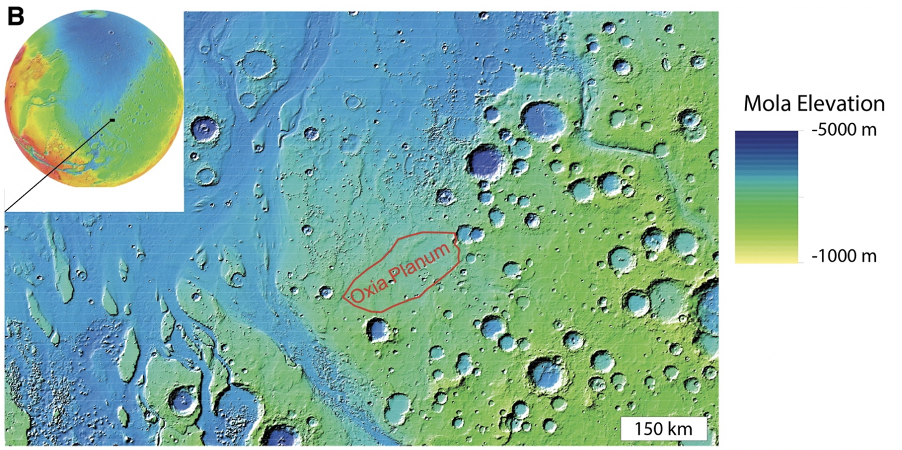

One thing we know about life is that it loves water. Images taken from cameras onboard satellites in orbit around Mars are able to give scientists hints to areas that could have once held water, such as dried-up river beds, craters that once held lakes, and possibly even an ocean. The northern hemisphere of Mars is in lower elevation compared to the south, hinting at the existence of a very large body of water. Oxia Planum is an equatorial region of Mars on the proposed coastline of this ancient ocean. Furthermore, Oxia Planum is rife with what are thought to be ancient river channels making it almost certain that water once flowed there.

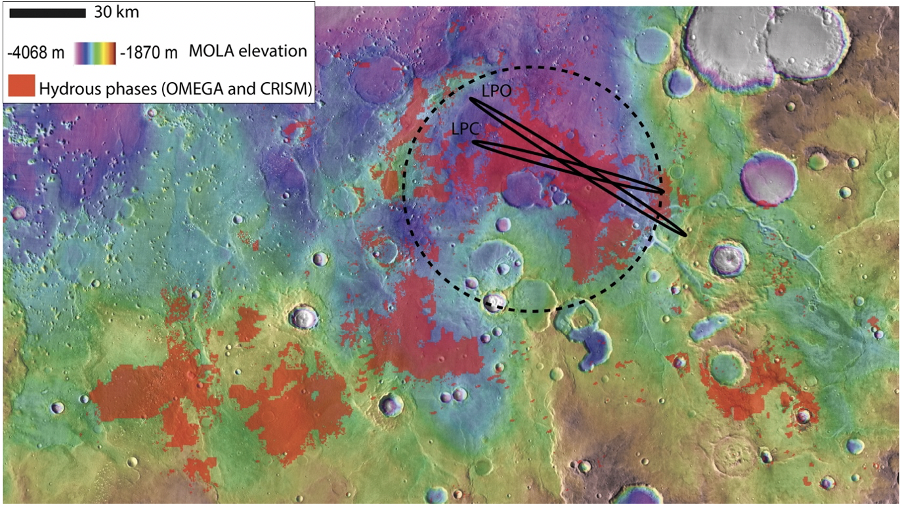

Ancient water flow on Mars can also be seen by multispectral data. Two satellite instruments capable of acquiring such data are CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars) onboard the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and OMEGA (Observatoire pour la Minéralogie, l’Eau, les Glaces et l’Activité) onboard the ESA Mars Express orbiter. These instruments view the surface in infrared wavelengths and allow the identification of minerals on the surface. Of particular interest is minerals that form from water interacting with and altering rocks, also known as hydrous minerals.

It turns out that Oxia Planum is covered in hydrous minerals, including clay and hydrated silica, suggesting that this area came into contact with water at least twice throughout its history. The oldest terrain here is a widespread clay-rich deposit ~4 billion years old that was later further covered by water, which created a deposit of hydrated silica. Samples of these hydrous minerals are of great importance to the mission as they could hold signatures of ancient life, also known as biosignatures.

If biosignatures – amino acids, organic matter etc. – were deposited within the hydrous minerals at Oxia Planum nearly 4 billion year ago they would likely be destroyed by radiation damage overtime. Luckily for the ExoMars mission, the hydrous mineral deposits at Oxia Planum were overlain by a dark protective layer, possibly an ancient lava flow, that may have prevented the decay of biosignatures. Overtime this layer has eroded to expose the hydrous minerals underneath whilst protecting any biosignatures throughout geological time.

Furthermore, the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover comes equipped with a 2-metre drill in order to access sediments buried within deposits. Scientists hope the depth of such samples will mean they will have been further protected from radiation overtime giving the mission the best possible chance to find evidence of life on Mars at Oxia Planum.

The answer to the question ‘is there life on Mars?’ is one that has been pondered for hundreds of years. Within the next decade, with data from NASA’s Perseverance rover and ESA’s ExoMars rover, that question may finally be answered.

Oxia Planum: ExoMars 2022 Landing Site by Emma Harris is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

One Reply to “Oxia Planum: ExoMars 2022 Landing Site”