Paper: Shallow lakes under alternative states differ in the dominant

greenhouse gas emission pathways

Authors: Sofia Baliña, María Laura Sánchez, Irina Izaguirre, Paul A. del Giorgio (2023)

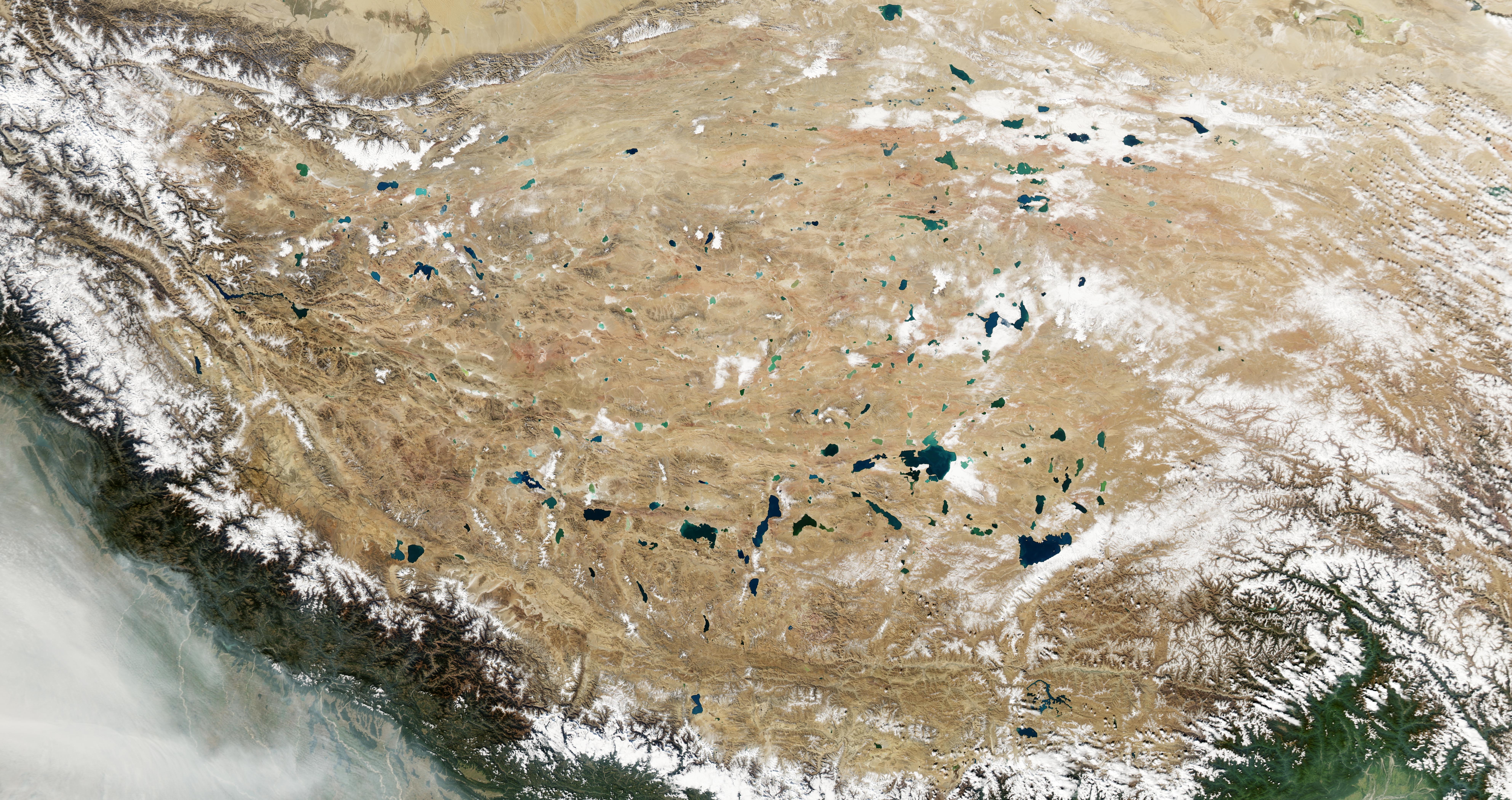

Imagine some of the most dynamic, ecologically important lakes in the world…. you are picturing a deep, wide lake, not something knee deep and murky, or so full of aquatic plants you can’t see the bottom, right? Well, perhaps you should; while they don’t always make the most inviting swimming holes, small, shallow lakes have an outsized importance in the cycling of carbon and other nutrients through the landscape.

Shallow depths tend to lead to warmer temperatures and more concentrated growth of algae and aquatic plants, not always the most desirable features for recreation. But what these lakes might lack aesthetically, they make up for with a massive contribution to the global carbon cycle. Combine the abundance of small lakes with a tendency for frequent mixing of the water column, and high rates of organic input from the surrounding watershed and small lakes pack a big punch in terms of cycling nutrients, including carbon, through pathways in both the water and lake bottom sediments.

These carbon cycling power houses are tricky to pin down because they can operate in what scientists call two different ‘stable states’: a murky, turbid state, dominated by algal growth that blocks the sunlight from reaching the bottom, and a clearwater state where plants anchored in the lake bottom sediments are dominant. A number of natural events, including floods, droughts, or changes in surrounding vegetation can lead to a ‘flip’ between states. Human activity can lead to a ‘flip’ as well, for example, in the Pampean Plains of Argentina, agricultural practices have added excess nutrients to the system, which tends to push lakes toward the murky, turbid state. The two lake states not only look different from the surface, but also have important differences in rates of photosynthesis, burial of organic material, and circulation in the water.

Knowing the importance of small lakes to global carbon cycling, a team in Argentina did a detailed investigation on how the different states impact carbon cycling and green house gas emissions. By monitoring sets of turbid and clear shallow lakes in the Pampean Plains over the course of a year, they found important seasonal differences in rates of carbon dioxide (CO2) diffusion into and out of water column, and in the flux of methane (CH4) from lake bottom sediments.

Through monitoring instrumentation suspended in the air above the lakes, as well as measurements taken in the water and sediments, researchers were able to observe weather-driven seasonal changes. The biggest differences were between winter and spring: cold, clear lakes tended to act as CO2 source. When the lakes warmed up, they started to move gas from the water into the atmosphere and became carbon sinks, while turbid lakes did the opposite.

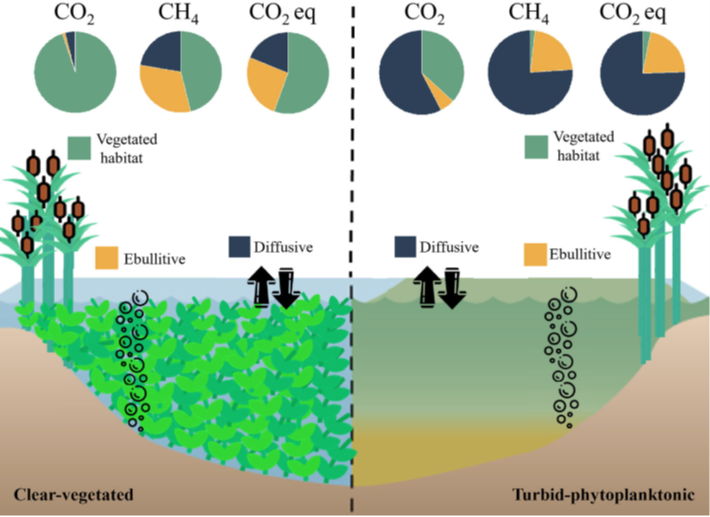

Figure 3 from Baliña et al. (2022) showing the different pathways and relative ratios for carbon flow in clear-water, vegetated lakes (on the left) compared to more green, or turbid, lakes with heavy algal growth on the right. In total, the total greenhouse gas emissions (or CO2 equivalents) for both lake states was similar, but came from different pathways in the lake.

Over an annual cycle, clear lakes had as much as 5 times the CO2 emissions to the atmosphere as compared to turbid lakes, mainly attributed to the vegetation. Turbid lakes, however, had a higher annual emission of CH4. On balance, the two groups of lakes had roughly the same total contribution to green house gas fluxes, but the seasonal variability and differences in carbon pathway are important to understand as we continue to learn more about these dynamic ecosystems and how they change over time.

One Lake, Two Lake; Green Lake, Blue Lake by Avery Shinneman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.