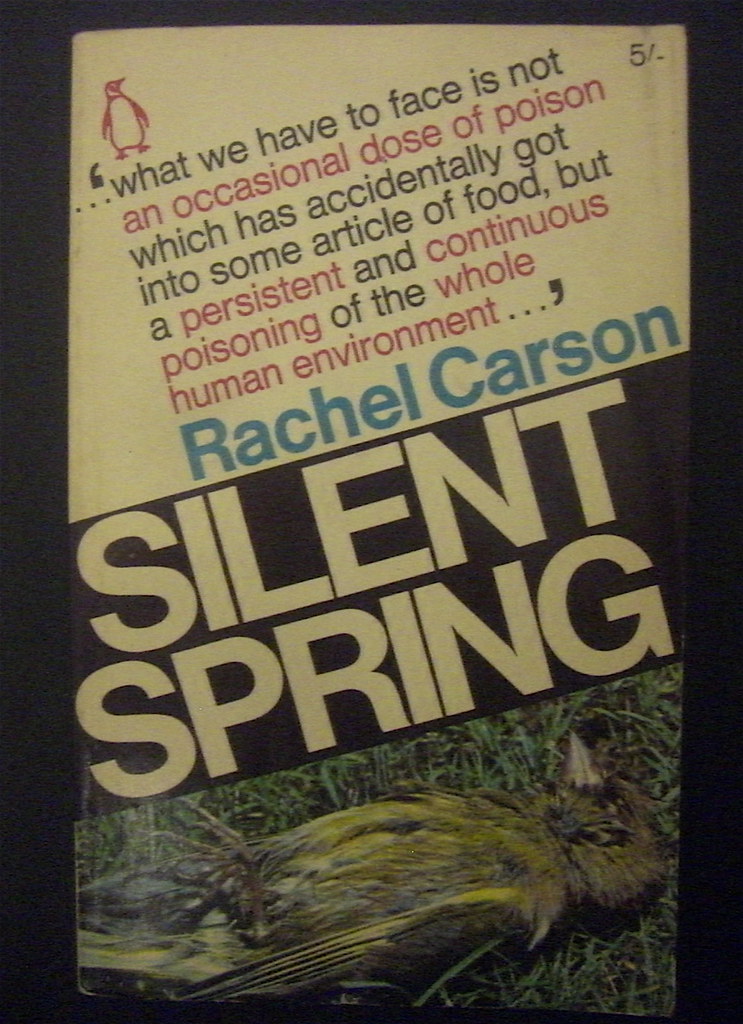

Featured Image: Carson’s pioneering work in 1962 made environmental issues a topic that could no longer be ignored. Photo by Frank Hebbert via. Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Book: Silent Spring (1962)

Author: Rachel Carson

We recently reached a milestone in our history: the amount of land used for farming is now declining, reversing millennia of expansion since early farming gave rise to larger civilizations. This has sparked a debate about how we should use remaining farmland – for example, to restore habitats – and how we can farm more efficiently. As our population continues to grow, and peak at the end of this century, we need to create more food from less land with a reduced environmental impact.

Rachel Carson is widely recognized for her vital role in raising public awareness of environmental issues with her 1962 book Silent Spring. The book sold more than a million copies in two years and inspired the first Earth Day in 1970, plus the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency the same year. The 1970s marked a turning point for the environmentalist movement, with the primary concern being the widespread spraying of harmful pesticides for agriculture – the focus of Silent Spring. As we consider the future of sustainable agriculture, this urgent need offers a great opportunity to revisit Carson’s pioneering contribution to the environmental cause. Despite being sixty years old, her timeless book can still help us confront such a complex issue.

The first chapter, titled A Fable for Tomorrow, paints an alarming picture of a degrading town, previously teeming with life, that has turned into a “shadow of death” where birds, livestock, fish, and fruit can no longer thrive, reproduce, or survive. This hypothetical town is Carson’s vision of an American town that has succumbed to the widespread use of pesticides.

After her beautifully-written introduction, she begins to outline a scientific argument demonstrating the harmful nature of indiscriminate spraying. Silent Spring summarises many scientific studies and ecological assessments, piecing together how negative impacts accumulate through the food chain and how industrial sprays, mainly DDT, cause long-term disruptions to the ecosystems they pollute.

In Chapter Four, she cites a particularly memorable case study of Clear Lake, California. DDD, another widely used insecticide, was measured at 1/50 parts per million (ppm) in the water. Yet, the fatty tissues in grebes (a bird species that bred nearby and ate fish from the lake) contained concentrations of 1600 ppm. This was due to a gradual accumulation of the chemical in their tissues from the fish they ate. The fish themselves preyed on plankton from the lake, which also accumulated harmful chemicals. Local authorities used DDD as a safer alternative to DDT and took care to avoid polluting the lake. They introduced DDD in diluted amounts following a detailed survey of the lake, and concentrations were measured consistently in the water to ensure they were safe. However, the local authorities failed to account for this accumulation despite their efforts to control spraying – and this oversight had an enormous impact on the local ecosystem.

There are many similar examples throughout the book. Carson devotes chapters to affected ecosystems and species, including groundwater, rivers, soil, plants, insects that aren’t direct targets of spraying, and humans. Throughout various natural cycles, e.g. the flow of groundwater into rivers and the accumulation of chemicals throughout the food chain, many areas with little to no spraying were also affected. The interconnectedness of nature is a major theme explored throughout the book and Carson notes how these complex relationships create vulnerability.

Carson also contends that the widespread use of insecticides is expensive and that there are often far more effective, cheaper alternatives, such as the introduction of natural predators to control pest populations. One such example is the successful use of biological pest control to minimise Japanese beetle populations, an invasive species that caused widespread disruption since it arrived in the US in 1916. Similarly, for many case studies where spraying has left its “shadow of death”, there is a counter-example highlighting successful efforts to manage insect populations without the need for insecticides.

I mentioned earlier that Carson played a significant role in advancing the environmental cause by revealing a relatively unknown science at the time to the public. Unfortunately, Carson never lived to see the impact of her transformative work. She passed away in 1964, after a battle with cancer, and before many of the reforms she inspired became policy. Several recommendations in the book, including funding more research into better pest control measures, regulating the pesticide industry, and relying more on biological field observations (to avoid scenarios like Clear Lake), were eventually implemented. DDT was even banned in the US in 1972 in a landmark decision following public pressure after the book’s release.

One of the themes that stuck with me after first reading the book is the importance of nature to humanity. We don’t just benefit from the food and water it provides, its beauty, or its economic value. A well-protected biosphere is intrinsically linked to our own health and well-being. Sixty years after Silent Spring, this is a lesson we must continue to push as nature faces more harm than ever, with many species in decline, in the face of climate change, habitat destruction, and unsustainable farming that still depends on harmful chemicals.

The Book that Launched the Environmental Movement by Jordan Healey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.