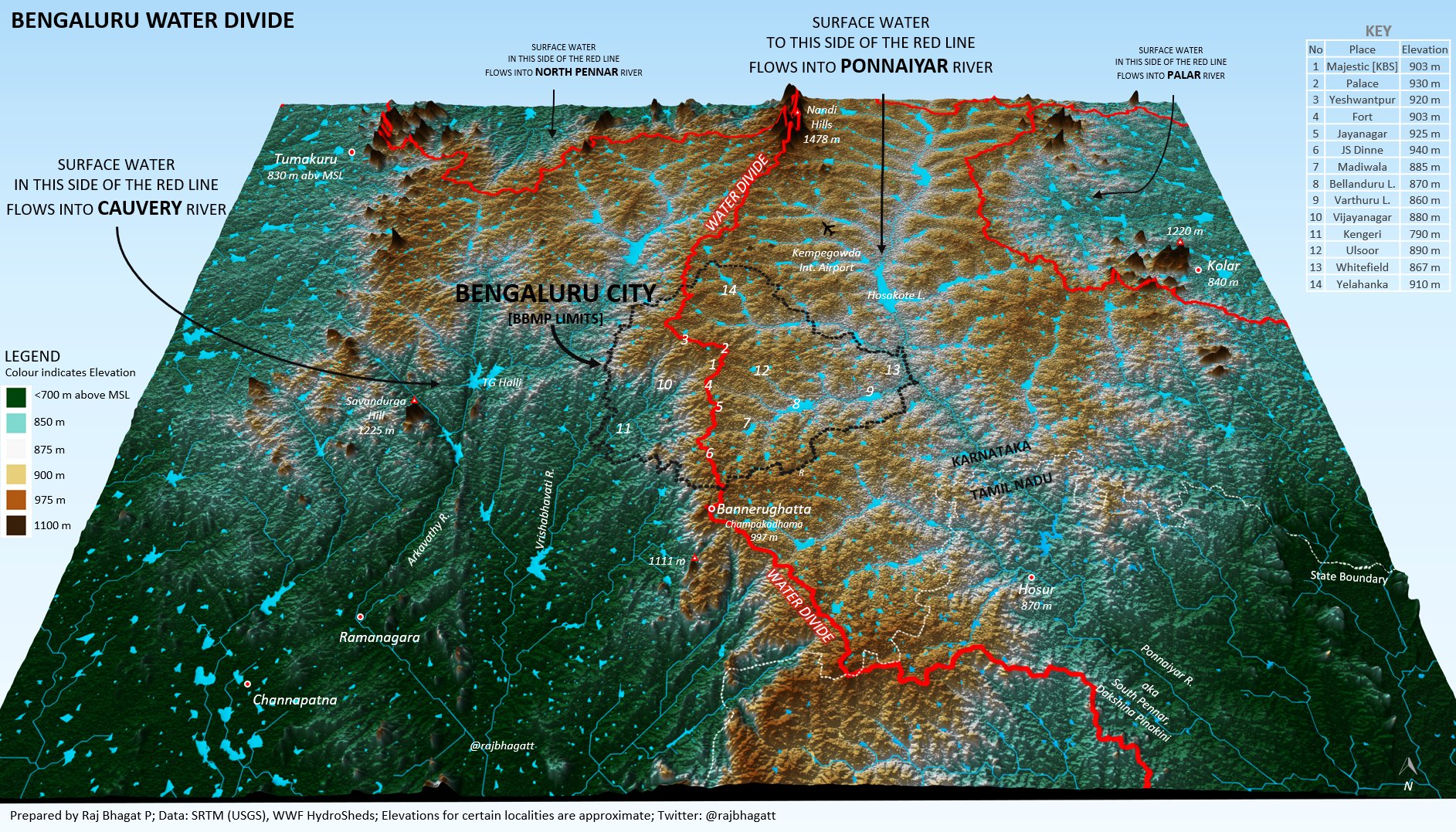

Featured Image: Raj Bhagatt P (published with permission from the author)

Castán Broto, V., Sudhira, H. and Unnikrishnan, H. (2021), WALK THE PIPELINE: Urban Infrastructure Landscapes in Bengaluru’s Long Twentieth Century. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res., 45: 696-715. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12985

Can a pipeline that runs through an urban landscape weave narratives of water usage through space and time? A beautiful article published in the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research captures some of the stories along the oldest pipeline in Bengaluru, South India. The narratives talk of the urban and rural divide, the patterns of urban sprawl, the pre-colonial water management, and the scarcity faced today.

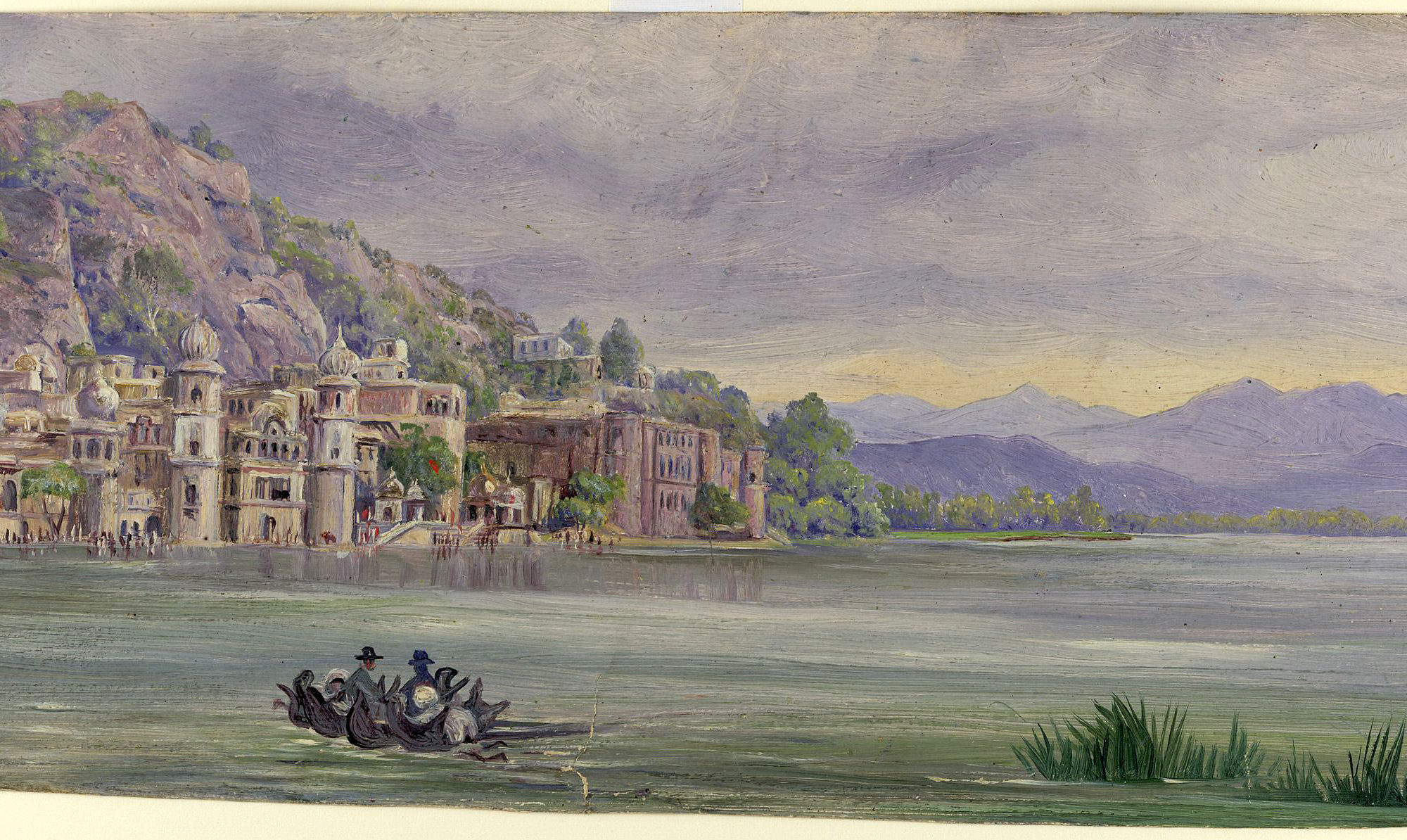

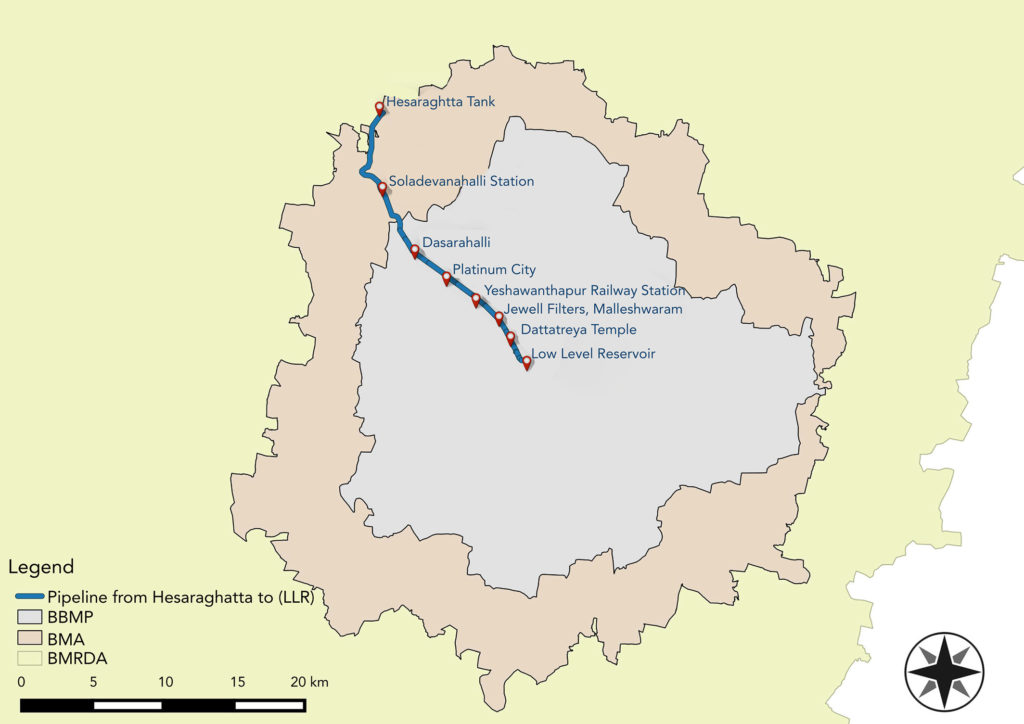

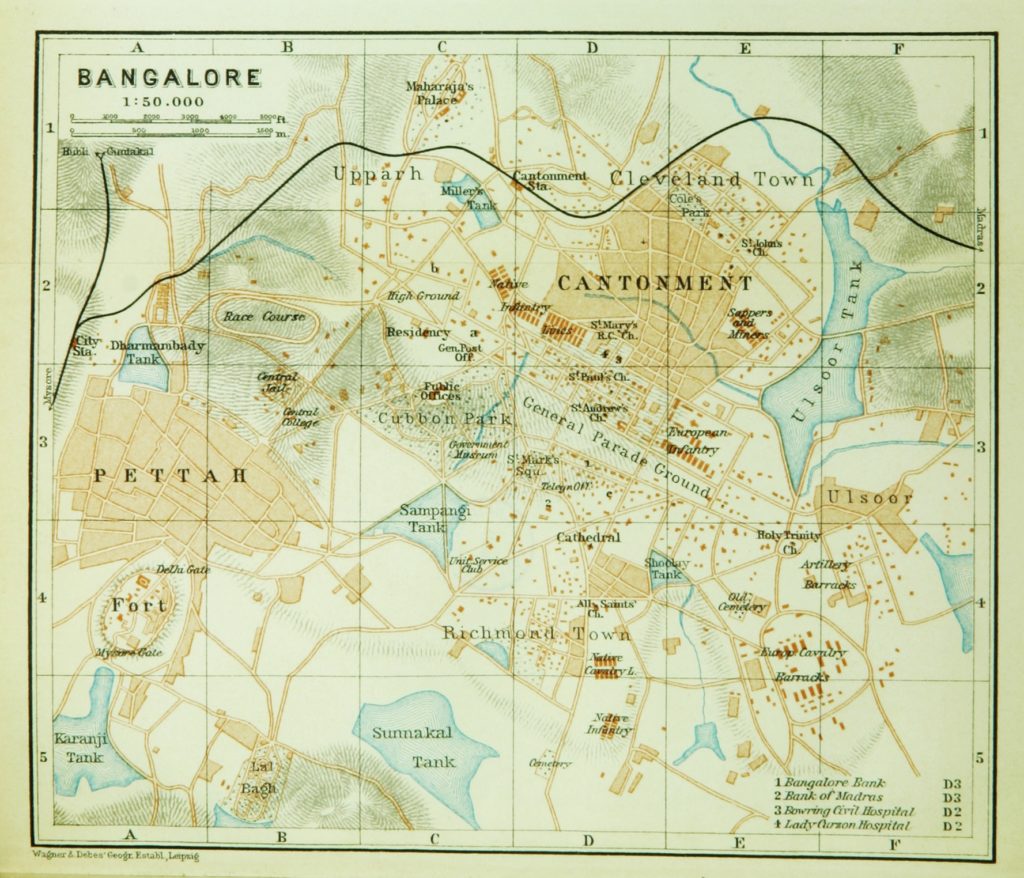

Before the pipeline, Bengaluru relied on an ancient network of seasonally-replenished tanks, reservoirs and open wells for its agrarian water supply. This network was engineered to harness the natural gradients of Bengaluru’s topography, and to ensure water reached different parts of the city. In 1894, the Chamarajendra waterworks laid down the first modern iron pipeline to source water from the Arkavathi river to Bengaluru’s colonial heart – and history was made. Based on old planning records and an analysis of historic maps, this pipeline today can be traced from the low-level reservoir at the heart of Bengaluru, passing through the neighbourhoods of Malleshwaram, Yeshwanthpur, and Dasarahalli, ending at the Hesaraghatta tank at the northwest corner of the city. Throughout history, the pipeline has affected the lives of people and other urban infrastructure along the way, and continues to do so.

In the 1960s, the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) was created to meet the demands of the city. Yet with the ever-expanding urban stretches and the burgeoning population, water scarcity is among the major challenges faced by Bengaluru today. Pipelines from Tarabanahalli, and from Shivanasamudra, along with the old one from Hesaraghatta, transfer water from the rural outskirts to the heart of Bengaluru. In addition, groundwater resources and some water from the Arkavathi river is carried by tankers into the city, to supplement the 6,000 public borewells, and roughly 50,000 residential borewells. Despite water conservation efforts like rainwater harvesting and recycling, the water scarcity in Bengaluru has begun to have ecological and environmental impacts – and the impact will be disproportionately felt by the low-income groups, who can not afford private borewells, nor the cost of long-distance transfers.

The article goes on to reflect on the historical, socio-economic, and political aspects of the neighbourhoods through which the pipeline flows – almost like a travelogue with a bitter note. As the pipeline networks developed, they created a set of conditions for residential and industrial development. Some neighbourhoods benefit directly from the pipeline, whereas some don’t, and over time the pipeline has further marginalized the poorer populations from receiving a good supply of water. These disparities will only get starker in the years to come. Residential overcrowding, land misappropriation, pollution, and increasing demand for industry and residences affect the efficiency of the water network and strain the groundwater resources. As more technological solutions are sought, the local ecologies that sustained these past water systems – such as agricultural patches that helped replenish tanks, the numerous rainwater-filled lakes that have since disappeared due to encroachment, or are severely polluted and littered, have been ignored.

The article underlines a harsh truth – Bengaluru never had enough water. If we are to strategize our water infrastructures again, we need new technological approaches, new resources or to reverse the direction of services from the peri-urban area to the centre of the city and vice versa, with due cognizance of encroachment and violations by existing and future development. The traditional system of tanks and wells needs to be integrated into the broader network of water resources to meet the needs of an ever-expanding urban nexus.

Pipe Dreams: stories of Bengaluru’s water supply by Devayani Khare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.