Authors: T.V. Ramachandra, S. Vinay, S. Bharath, M.D.Subash Chandran, and Bharath H.Aithal

A catchment or watershed represents an intricate network of streams that coalesce into a river. In ecology, river networks are considered as ecosystems since they facilitate interactions between organisms and their environments. A healthy river ecosystem sustains the biodiversity of fringing forests and aquatic habitats, and enhances the landscape’s resilience to water resource development, droughts and climate change. Rivers provide water for domestic, agricultural and industrial use, and sustain native vegetation which in turn regulates the water cycle, and provides forest-based goods and services.

Image: public domain

In India, rivers are revered, and some even have rights as ‘legal persons’, yet they aren’t considered to be ecosystems, and are among the most threatened features of our landscape. Nowhere is the threat more acutely felt than in the Western Ghats – the world’s most populated biodiversity hotspot. The Western Ghats represent a mountainous ridge running along the western fringe of the Indian peninsula – its river network irrigates millions of hectares and sustains over 245 million people. In the past few decades, changes in land-use patterns, wastewater discharge, reservoir construction, and water abstraction have affected the natural flow of the rivers. Yet without documenting how such unplanned development affects livelihoods, ecosystem services, and biodiversity, authorities aren’t likely to take note or responsibility.

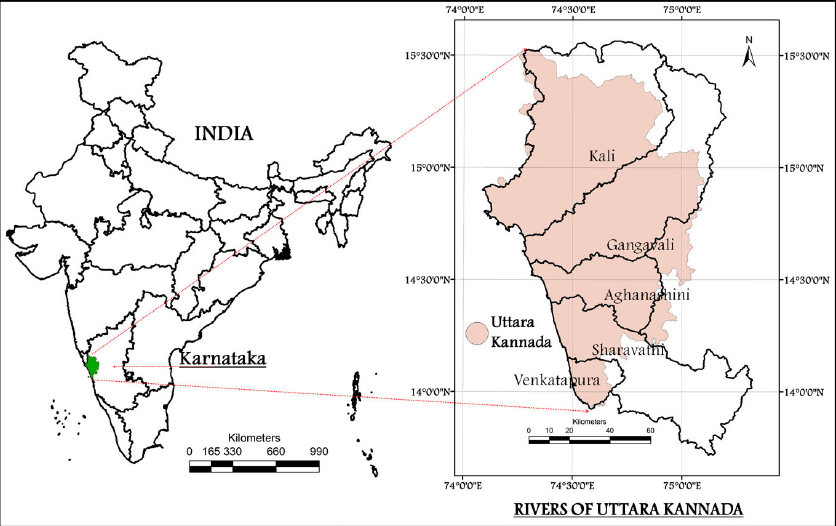

To this end, in May 2020, researchers from the Centre for Ecological Science (CES), published a paper in Current Science. The study details the land-use analyses of four Western Ghats river systems, namely, Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavati, located in the Uttara Kannada district, in the state of Karnataka, India. With the aid of temporal remote sensing data, the researchers assessed changes in forest and other vegetation cover. Water samples collected from different locations in each river were used to assess pollution levels. The authors calculated the water requirements of different crops, human habitations, and their livestock to determine the societal water demand.

Image sourced from the paper by Ramachandra et al.

The study by Ramachandra et al, showed that from 1973 to 2018, there was a marked decline in forest cover in the Uttara Kannada district from 74.19% to 48.04%, with evergreen forests reduced to less than half of their former acreage. When native forests are replaced by other vegetation or habitation, it creates a patchy, fragmented tapestry that can result in disruptions in the biogeochemical, nutrient and water cycles across the system. In this region, many factors contributed to the fragmentation of forests: dam construction (mainly in the Kali river basin) without restoration measures, increased monoculture plantations, conversion of forest land for agriculture, horticulture, or private plantations, habitation or development, the establishment of forest-based industries, and a nuclear power plant at Kaiga.

With this data, the authors calculated the eco-hydrological footprint – a measure of how well river systems can meet ecological and human needs. The eco-hydrological footprint values indicated that forest cover directly affects the seasonality of streams, nutrient availability, and biodiversity, especially endemic species. Contiguous forests have more perennial channels than degraded patches. Perennial streams have higher carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous levels, leading to a nutrient-rich forest cover that supports richer biodiversity, and more endemic flora and fauna. The researchers documented the gross annual incomes and profits (normalised by hectares cultivated) and found that perennial catchments support more profitable agriculture and freshwater fishery-based livelihoods than seasonal ones.

Image: public domain

Recently, India’s policy-makers stated that freshwater flowing into the sea is a waste of a precious natural resource. The authors beg to differ. In an era of rampant, indiscriminate development in river catchment areas, their study provides an understanding of the hydrological, ecological, and social linkages to help decision-makers better plan an integrated river-basin management programme.

Where the rivers flow: India’s catchment crisis by Devayani Khare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

hi there, your post is so good.Following your posts.