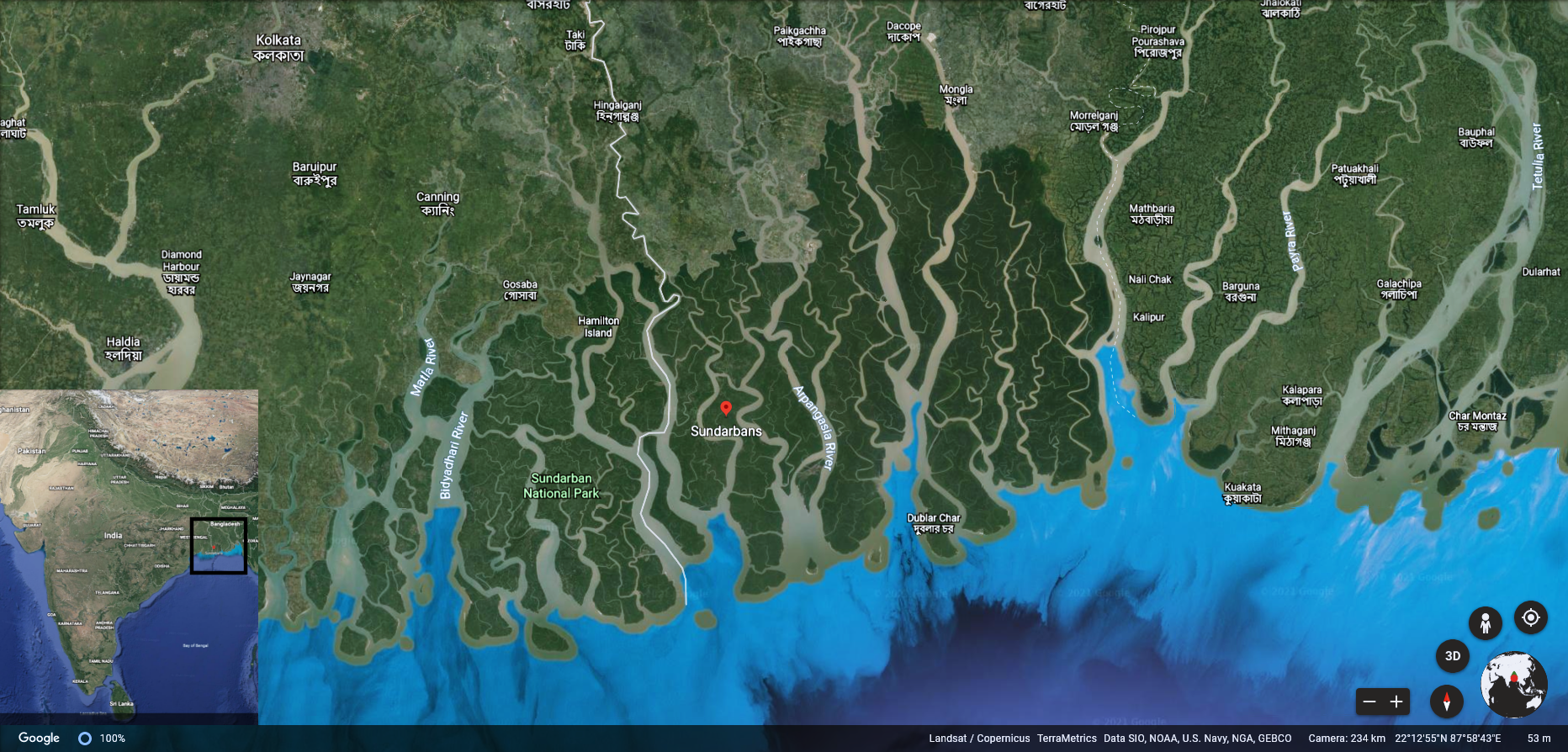

Mid March 2021, I set out with 2 other wildlife enthusiasts to explore the Sundarbans delta in east India. The 3-hour journey from Kolkata city, on a busy road fringed by industrial towns tapered off at Gadkhali port – civilization’s last ‘land’ frontier before the largest continuous mangrove stretch in the world. We arrived after dusk, boarded our boat (with a crew of 2 naturalists, 3 boatmen, and a chef!), and were adrift upon dark waterways guided by twinkling village lights. In our haste, we thought little of just how ‘remote’ this wilderness was.

The next morning, we woke up to a different world – sheer, open stretches of water that melted away into the morning haze. Nothing quite prepares you for the Sundarbans, one imagines river deltas as narrow channels of water interrupted by little islands, yet that morning, with no other islands visible on the horizon, it seemed more like a sea than a river. For the next three days, we’d be exploring the Sundarbans – among the most difficult terrains for civilization and wildlife watching, from dawn to dusk.

Photo credits: Devayani Khare

Formed as several rivers, including the Hooghly, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna, and other channels with different local names, combine and flow towards the sea. The Sundarbans named for the ‘sundari’ trees (Heritiera fomes) + ‘ban’ the local word for forests, covers roughly 10,000 sq. km (3900 sq. miles), partly in India and partly in Bangladesh. Of the delta’s 104 islands that fall within India’s territory, just a handful of islands are inhabited, while the rest form the buffer and core zones of the Sundarbans National Park. With its incredible, fragile biodiversity, the Sundarbans was also declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987.

As idyllic as remote islands seem, the Sundarbans has always been a dangerous landscape, and not just on account of the tigers. Rapid coastline erosion, riverbanks and islands shape-shift due to the accumulation or removal of sediment or silt, and extreme events like cyclones are commonly experienced in the Bay of Bengal [1] – the sea that the delta opens out into. Cyclones like Amphan (May 2020), Fani and Bulbul (both 2019) were among the 13 supercyclones this area has witnessed in the past two decades [2]. Research across the world has shown that dense mangrove vegetation reduces the wave height and wave energy during storms[4], and can thereby dampen the effect of extreme events like storms and cyclones. Yet, deforestation has thinned out the ‘protective shield’ of mangrove, and the ‘sundari’ trees which the forests were named after have been declared endangered by the IUCN.

There is less than a century’s worth of geoscience research available for the region, and it indicates that the delta is in constant flux: sediment building and eroding away at its banks. This makes embankments and other coastal engineering solutions unviable, and farming is a poor prospect[3]. Rising sea-levels caused by climate change may further fragment the habitat and cause greater salinity in the water, both of which will adversely affect the fauna and flora. The short data record makes it difficult to understand long-term cycles for better mitigation in the near future.

Photo credits: Devayani Khare

For locals, livelihood options are limited: near-subsistence farming or fishing (saltwater fish, shellfish, and crabs), boat-operated trade with the mainland, timber-felling (most of it illegal), honey, fruit, resin and medicinal plant extraction governed by the forest authorities and forest range services with a high risk of man-wildlife conflicts. Fly ash trade with Bangladesh flourishes, but as Kolkata is the major hub of operations with the Sundarbans merely a thoroughfare, there are few local job opportunities. However, in recent years, tourism within the delta has emerged as an economic champion: encouraging private investment in infrastructure, accelerating development with over 30 hotels and resorts ranging from economic to luxury, and the promise of further expansion.

Yet tourism development is a two-edged sword: in India, it has often been blind to the carrying capacity, local needs, and risks of a destination. The recent, mid-March 2021 election drive saw promises being made by the central government – Rs 2 lakh crore/trillion (that’s over 13 billion USD!) investment to develop the Sundarbans into the most advanced region in the West Bengal state. Even if this is empty political rhetoric, development of the Sundarban delta is an imminent threat – as not all of it will consider the ecological role of mangroves, the complexities of sediment transfer, the storm-dampening effects nor the local socio-economic and political context.

Photo credits: Devayani Khare

Over the three days, we cruised along the Sundarbans. Wildlife sightings were few, and far between – yet offered rare glimpses into the resilience of creatures in this adverse, brackish landscape. Ever so often, we encountered holidaymakers and casual tourists: there were more of them than the wildlife enthusiasts, reflecting what tourism development would mean for the Sundarbans. I believe everyone should have access to a destination, however sensitisation, awareness, and education is a crucial part of tourism, especially in landscapes as fragile as deltas. In this context, geoscience can lay the foundations to ensure biodiversity, people, livelihoods, and infrastructure are resilient to environmental change and natural hazards, and how tourism can be beneficial in the long-term.

Cited Literature:

[1] Dasgupta, Susmita, David Wheeler, Md. Istiak Sobhan, Sunando Bandyopadhyay, Ainun Nishat, and Tapas Paul. 2020. Coping with Climate Change in the Sundarbans: Lessons from Multidisciplinary Studies. International Development in Focus. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1587-4. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

[3] Sunando Bandyopadhyay, Dipanwita Mukherjee, Sima Bag, Dilip Kumar Pal, Rabindra Kumar Das, and Kalyan Rudra. 2004. 20th Century Evolution of banks and islands of the Hugli estuary, West Bengal, India: evidences from maps, images and GPS survey. Geomorphology and Environment.

[4] McIvor, A.L., Spencer, T., Möller, I. and Spalding. M. (2012) Storm surge reduction by mangroves. Natural Coastal Protection Series: Report 2. Cambridge Coastal Research Unit Working Paper 41. Published by The Nature Conservancy and Wetlands International. 35 pages. ISSN 2050-7941. URL: http://www.naturalcoastalprotection.org/documents/storm-surge-reduction-by-mangroves

Adrift along the Sundarbans mangroves, east India by Devayani Khare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.