Feature Image: Bald Eagle. Image from Wikimedia.

Article: Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy

Authors: Steffen Breinlinger, Tabitha J. Phillips, Brigette N. Haram, Jan Mareš, José A Martínez, Pavel Hrouzek, Roman Sobotka, W. Matthew Henderson, Peter Schmieder, Susan M. Williams, James D. Lauderdale, H. Dayton Wilde, Wesley Gerrin, Andreja Kust, John W. Washington, Christoph Wagner, Benedikt Geier, Manuel Liebeke, Heike Enke, Timo H. J. Niedermeyer, Susan B. Wilde

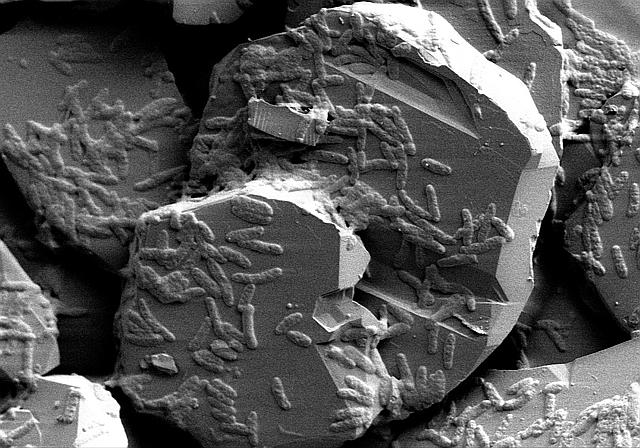

Over the winter in 1994-1995, the largest undiagnosed mass mortality of bald eagles in the USA occurred at DeGray Lake in Arkansas. In total, 29 eagles were found dead and another 26 were found in the following winter. Other sick individuals were observed overflying perches or colliding with rock walls. Autopsies revealed open spaces called vacuolar lesions in the eagles’ brains and spinal cords. Since this incident, waterbirds with the same neurological disease have been discovered throughout the southeastern USA, which resulted in a severe loss of motor functions and ultimately death in American coots, ducks, geese, and various birds of prey. The new disease was coined Avian Vacuolar Myelinopathy (or AVM).

Since the first outbreaks in 1994-1995, the cause of AVM outbreaks has puzzled scientists. One commonality between all AVM outbreaks was that they were located on or near man-made water bodies; however, the analysis of the lakes and dead birds recovered from outbreak areas did not contain any chemicals or pathogens that were previously known to cause vacuolar lesions in mammals or birds. Moreover, coots and mallards released into AVM outbreak areas developed the disease, but housing healthy and sick birds together outside of AVM outbreak sites did not cause the disease in healthy birds. These results suggested that a novel environmental neurotoxin rather than a pathogen was the cause of the disease. Even then, the identity of the toxin eluded scientists for over 25 years. Now, through a feat of scientific detective work, AVM has been linked to a novel neurotoxin produced by a newly discovered species of cyanobacteria. How did researchers finally solve the mystery?

Continue reading “Mysterious Eagle Deaths Linked to a Newly Discovered Cyanobacterial Toxin”