Feature Image: Huge amounts of waste symbolise the impact of human activity on the Earth System. Public domain image by Antoine Giret

Authors: Jan Zalasiewicz et al.

Journal: Earth’s Future

We are now entering a new geologic time due to the planetary-scale impact of human activity. The Anthropocene is widely accepted as this new epoch, but debate is still ongoing about its scientific basis and when this new epoch began. As so many different disciplines are involved in defining and characterizing the Anthropocene, it has become difficult to properly define. A recent paper by Jan Zalasiewicz and colleagues aims to provide context as the broad subject spills over into other areas of science, art and the humanities. They emphasise that future studies should stick to the original stratigraphic and Earth System Science meaning of the term to avoid confusion around the term.

The term “Anthropocene” was coined by environmental chemist Paul Crutzen, who claimed the increasing impact of humanity on Earth’s atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and other components of the “Earth System” has caused us to enter a geologically distinct epoch from the Holocene, which began following the last glacial ~11,600 years ago. Chronostratigraphy, the science of correlating rock units in space and time, involves maintaining the geologic time scale through the International Commission on Stratigraphy, which requires a panel of experts to vote on whether a new subdivision of time should be defined and where its geologic base should be. While a new subdivision of time should have a global marker, one location is assigned a “golden spike” to identify it as the main basis for correlation and to make a new boundary official. Because there are 4.6 billion years of Earth history, it’s useful to divide time into eons, eras, periods, epochs, or ages (from longest to shortest). This approach is often compared to how taxonomists and paleontologists categorize life forms into kingdoms, phylums, classes, etc.

Changes in geologic time usually follow environmental changes that can be easily identified by a marker – for example, the first or final appearance of a fossil species, or a change in the rocks’ chemistry following warming or cooling (although for more recent times ice cores, tree rings, and other materials can be used as archives). A rock unit, or other archive, must meet specific criteria to be considered a candidate for a golden spike to be allocated. The scale of the event determines the rank of the time category. For example, the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous was an era-defining event but not quite an eon-defining event. Epoch-ranked events, such as the proposed Anthropocene, only usually occur once every million + years and, since the current Holocene began only 11,600 years ago, the concept has attracted some controversy.

The Anthropocene Working Group, a task group of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (the part of the International Commission responsible for the geologic timescale from 2.6 million years to the present), has been assessing the markers for the base of the Anthropocene, to decide if it is to be officially recognized as a new epoch. They determined that the mid-1950s is the most fitting origin as the timing coincided with immense global population increase and consumption of resources. Additionally, the fallout from several nuclear bomb tests carried out by the US and Soviet governments will leave an imprint in the geological record that will survive for millennia. Other secondary markers from around this time include “technofossils”, particulates deposited following coal burning and car use (both increased massively during the 1950s), and the biomarkers provided by rapid species declines and invasive species emerging in new regions. These definite events in the 1950s provide the sharp geologic boundary that’s essential to correlate rocks to their respective periods, defining the new epoch of the Anthropocene.

As the concept has such widespread appeal across several disciplines, many different interpretations of it exist. Some define the onset of the epoch as following societal changes rather than the geologically-distinct changes that will remain identifiable thousands or millions of years into the future. For example, studies in archaeology/anthropology have identified the point of origin as the early farming developments that gave rise to civilization; which does not meet the criteria for a geological/Earth System Science marker (different civilizations emerged at different points in space and time so there is a lack of distinct, global marker). Historians may point to the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas or the invention of James Watts’ steam engine as they both mark pivotal moments in our history regarding our environmental impact (global trade and industrial activity). These, similarly, do not record geological changes, despite being major events in our history.

Climate scientists, notably Mark Maslin (UCL) and Simon Lewis (UCL & University of Leeds) have pointed to the Orbis Spike, a sharp decline in CO2 levels (recorded in ice-cores) that occurred in 1610. This decline was triggered by genocide and diseases that impacted native American populations following European colonization in the region – fewer people meant less farming, so trees were able to regrow and remove CO2 from the atmosphere. This is, again, an interesting link between social changes and their impact on the environment; however, it is difficult to correlate the Orbis spike between rocks and other long-lasting archives globally. Moreover, this measurement fails to capture the scale of human activity in the same way as the CO2 measurements since 1950.

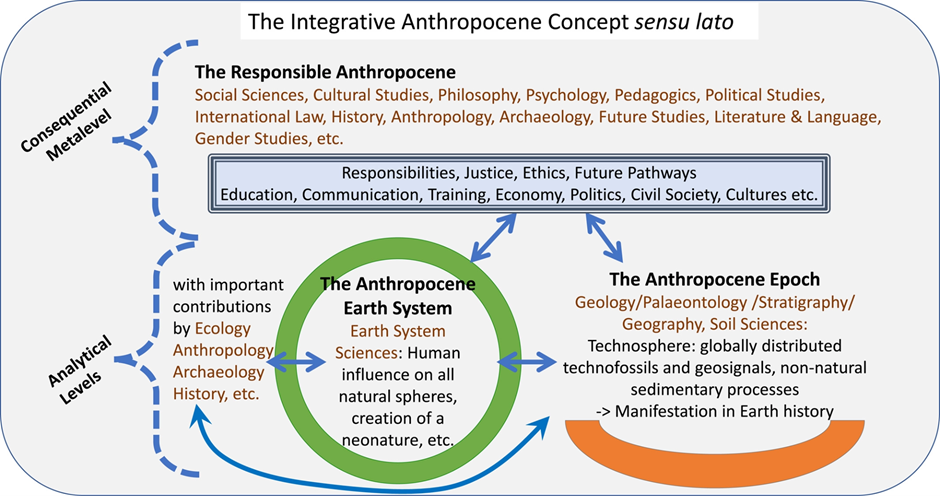

Many different hypotheses exist surrounding the origin of the Anthropocene, if we accept that we are living in an epoch that is distinct from the Holocene, as Crutzen initially outlined. It is therefore important to make sure that the discussion moves in a direction that avoids misrepresenting its meaning when trying to understand the interactions between humans and the environment through time. Care must be taken though to avoid flexible use of a meaning that lacks context, hence the need for clarification with the Zalasiewicz et al. paper. Their works presents a framework (figure 1) that divides up the Anthropocene concept into analytical and consequential levels which are both centered around the original meaning, benefiting all who are interested in the concept from its underlying causes to its place in future discussions both in public and academic spaces.

Defining and Contextualising the Anthropocene by Jordan Healey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.