Feature image from Pixabay

Article: Rhetoric and Frame Analysis of ExxonMobil’s Climate Change Communications

Authors: Geoffrey Supran & Naomi Oreskes

It’s no secret that ExxonMobil is a major architect of the climate crisis. The oil giants have allocated incredible amounts of time and resources to undermining climate science while continuing to pollute the planet. Now, a recent One Earth publication by Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes unpacks the way Exxon has so successfully spread propaganda while borrowing techniques from another destructive industry: that of tobacco. Exxon and other oil companies (often supported by powerful right-wing think tanks) have embarked on a propaganda campaign that has morphed from outright denial into a campaign aimed at distracting us, dividing political opinion, and convincing us that climate action is hopeless. Supran and Oreskes delve into the evolution of Exxon’s harmful contribution to this narrative.

This isn’t the first research from Naomi Oreskes exploring this type of propaganda. The tobacco industry famously denied the links between smoking and lung cancer for decades and later did the same when passive smoking was highlighted as a major health concern by scientists; in Oreskes’ and Erik Conway’s book Merchants of Doubt, the comparison between the tobacco industry and climate change denialism is a major theme, so it’s no surprise to see these arguments fleshed out more in this study in One Earth.

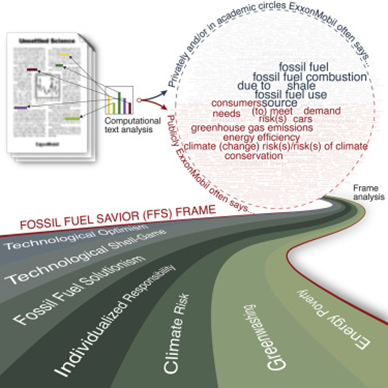

The One Earth study is a frame analysis, where “frame” refers to the subtle ways that an organisation constructs and defines a political issue. In the case of this study, the focus is on language choices and framing in 180 Exxon documents, including 72 contributions to peer reviewed journals, 32 internal documents and 78 New York Times advertorials. Oreskes and her co-author use a machine learning approach called Latent Dirichlet Allocation, which unravels major themes across several bodies of text by searching for patterns that emerge due to the authors’ language choices and which shape the overall narrative. 3 main frames are identified:

- The Scientific Uncertainty Frame, which emphasises that more research is needed before governments regulate the industry.

- The Socioeconomic Frame, which states that regulations are harmful to the economy and that companies should essentially regulate themselves.

- The Fossil Fuel Saviour Frame, which portrays fossil fuel companies as being instrumental in the fight against climate change, typically through their research into geo-engineering e.g. carbon capture and storage. Individual responsibility for climate change is emphasised.

Their analysis concludes that Exxon communication since the mid-2000s has taken the shape of a fossil fuel saviour (FFS) frame, which cleverly advances their agenda and stifles government regulation and public scrutiny, whereas earlier communications, dating back to the late 1970s, were more in line with the other frames. Importantly, the FFS frame shifts the responsibility of climate change to the consumer. Oil companies are, in their opinion, just meeting the demand for their product, while their customers are to blame for consuming so much. Figure 1 illustrates the main themes associated with this frame and the key terms that are used in private and academic circles vs. in public.

Figure 1 Graphical abstract for the Supran & Oreskes (2021) study highlighting the ways a fossil fuel saviour frame is advanced and the key words choices that undermine climate action. Image reprinted with permission from Supran & Oreskes, 2021, One Earth 4, 696-719

One interesting example from the study is the discrepancy between advertorials and peer-reviewed scientific papers or internal documents when it comes to acknowledging fossil fuels as a driver of climate change; the research and internal documents acknowledge climate change while the advertorials do not. The New York Times’ audience is far larger than that of most peer-reviewed research papers. This discrepancy between their advertorials and science means public discourse is influenced more by a skewed representation of the science than the science itself – another major theme in Merchants of Doubt. Historically, when scientists want to correct the record on misinformation, they are not effective at reaching mainstream audiences and are often limited to niche scientific journals and other inaccessible types of media.

Supran and Oreskes also highlight how Exxon communications emphasise the use of the word “risk(s)”, to downplay the urgency of action needed, and “demand”, to shift blame onto the individual rather than the company. The science itself has been clear for several decades that climate change is a reality, not a risk, but Exxon representatives have carefully chosen these words to cast doubt over the scientific consensus and individualise the responsibility for climate change.

It is difficult to imagine how much better the world would be if we had taken advantage of this head start and implemented the right policies to combat climate change back then. Over half of all atmospheric CO2 released since 1751 was emitted in the last 30 years and now other people (mostly those living in countries that have contributed less to the issue in the first place) will have to suffer the ramifications. Instead, Exxon has helped maintain a carbon lock-in where fossil fuels remain widely relied upon. The work of Supran and Oreskes is essential to developing our understanding of how conflicts of interest and the profit motive can influence the public discourse regarding climate change, and stifle action for decades, just like the tobacco industry did. In a world where misinformation is more easily spread through online echo chambers, it’s vital that we understand how propaganda is manufactured and educate people to spot its key components. Only if scientists, activists, and politicians can match the aggressive marketing of the oil lobby will we be able to combat climate change.

ExxonMobil: A Case Study in Climate Change Propaganda by Jordan Healey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.