Papers: Changes in humpback whale song structure and complexity reveal a rapid evolution on a feeding ground in Northern Norway; Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Song on a Subarctic Feeding Ground

Authors: Saskia C. Tyarks, Ana S. Aniceto, Heidi Ahonen, Geir Pedersen and Ulf Lindstrøm

Featured Image: Humpback whales swimming near Tonga. Photo by Elianne Dipp.

US Navy engineer Frank Watlington was searching for Russian submarines in the 1950s when his underwater microphone picked up some otherworldly noises: humpback whale singing. He was amazed to realize that the whale vocalizations were arranged in an intricate pattern that repeated itself in a song-like manner, with a similar structure to music composed by humans.

Also like humans, whales are thought to imbue their music with social signals. Exactly why and how they do this is a hot topic in whale research. Previous work suggested that singing is an important part of the mating process, and until recently, male humpback whales were thought to only sing at breeding grounds close to the equator. This changed in 2021 when Tyarks et al. documented singing at a high-latitude feeding ground near Norway. In their 2022 follow-up paper, the authors found that the complexity of these songs changed rapidly over the course of a year, shedding light on how singing at high-latitude feeding grounds might play a role in humpback whale mating.

The authors used whale recordings from the Lofoten-Vesterålen Ocean Observatory’s underwater microphone, which is attached to the ocean floor about 20 km offshore from the Lofoten Islands, Norway. This location is a stopover point along the migration routes of different humpback whale populations.

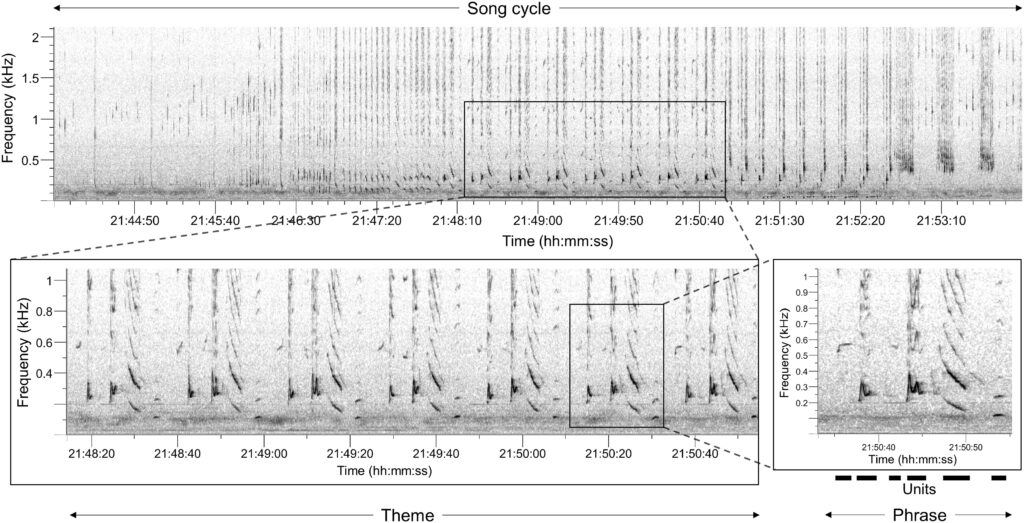

The team identified 15 song sessions from January 2018 through January 2019. To quantify how singing changed through the year, the scientists transcribed the recordings into spectrograms. Like sheet music for whales, a spectrogram is a visual representation of the song where each unit (e.g. each wail, moan, or grumble) has a unique shape according to its frequency and duration. Whales repeat a song many times during a song session, which can last up to a day and is shared by the entire population.

The scientists compared songs using a method called the Levenshtein Distance (LD). The LD calculates the number of differences between two spectrograms—that is, the number of units they would have to swap in order to turn one song into another. They found a steady evolution in song composition during the study period. These changes arose gradually and in a coordinated manner, with all singers adapting in near-unison.

Further statistical analysis showed that the songs became more complex during the mating season. In January 2018, the songs were short and simple, containing as few as 100 units. By April, the songs comprised up to 500 units, making them considerably longer and more complex. There seemed, however, to be a limit to how much the whales could learn in one year. The songs in January 2019 were much shorter, more in line with the complexity observed in January of the previous year.

If singing is used to attract mates, then it seems it’s not just hitting the right notes, but being able to pick up new notes that matters. The authors hypothesized that singing progressively more complex songs is a way for male whales to demonstrate they are quick learners and therefore good mating partners. This would also mean that high-latitude feeding grounds serve a dual purpose as an alternative reproduction site for whales who do not to migrate.

More observations are needed to confirm if it is true that whales who sing more complex songs enjoy higher reproductive success. The jury is also still out on whether singing serves social functions other than mating. Nevertheless, this Norwegian feeding ground is proving to be a multifaceted hotspot for humpback whales, serving as a place to eat, sing, and even possibly mate.

Humpback Whale Singing at a Norwegian Feeding Ground © 2023 by Shannon Bohman is licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International