Paper: Evolution of modern river systems: an assessment of ‘landscape memory’ in Indian river systems

Authors: Vikrant Jain, Sonam, Ajit Singh, Rajiv Sinha, S. K. Tandon

“A river cuts through rock not because of its power, but because of its persistence.”

James N Watkins

In geomorphology, the persistence of rivers is etched into the very landscape – a memory of the forces that once shaped it, and continue to do so, slowly, and inexorably. Landscape memory, as Gary John Brierley once wrote, is the imprint of the past upon contemporary landscapes, which include geologic, climatic, and anthropogenic factors.

The rivers of the Indian subcontinent bear witness to forces that shaped them over millennia – and a recent publication in the Journal of International Geosciences traces the evolution of India’s river systems at different time scales.

Landscape memory is shaped by:

- The tectonic cycle of mountain-building, volcanism, and erosion, which dictates the elevation, slope, and geology of a river landscape – as also the energy of a river.

- Geologic factors like rock formations, their erodibility, and signs of weakness like faults and lineaments, which affect the shape of the river basin and the amount of eroded material or sediment that can be carried downriver.

- Precipitation which controls the amount of water that flows through a river system, across seasons, and centuries.

Based on these factors, the authors of the paper classified India’s river basins into 6 types:

Ever wondered why certain rivers are revered in India – perhaps, because they have witnessed the birth of mountains? Ganga, Bhagirathi, and Alaknanda rivers, among other antecedent large Himalayan rivers maintained their course, even as the Himalayas folded and uplifted beneath them, by carving their way through bedrock. Originating near collision zones, these rivers fuelled by glacial melts and monsoons, carry a lot of water and sediment downslope.

Photo credit: Tarkeshwar Rawat (CC BY-SA)

The Himalayan foothills-fed rivers of Ramganga (India), and Baghmati (Nepal) rivers originate at the base of the Himalayas. They are sustained by heavy monsoon precipitation and sediment from the lower Himalayan range, the Siwaliks and irrigate alluvial plains as they flow towards the sea. Characterised by frequent floods and highly meandering channels, which often break away into temporary channels (that are later abandoned) and crescent-shaped lakes, these rivers hint at a frequently shifting nature – a characteristic that severely affects the urban and agricultural landscape of the Terai belt.

Photo credit: Pratap Baniya (CC BY-SA)

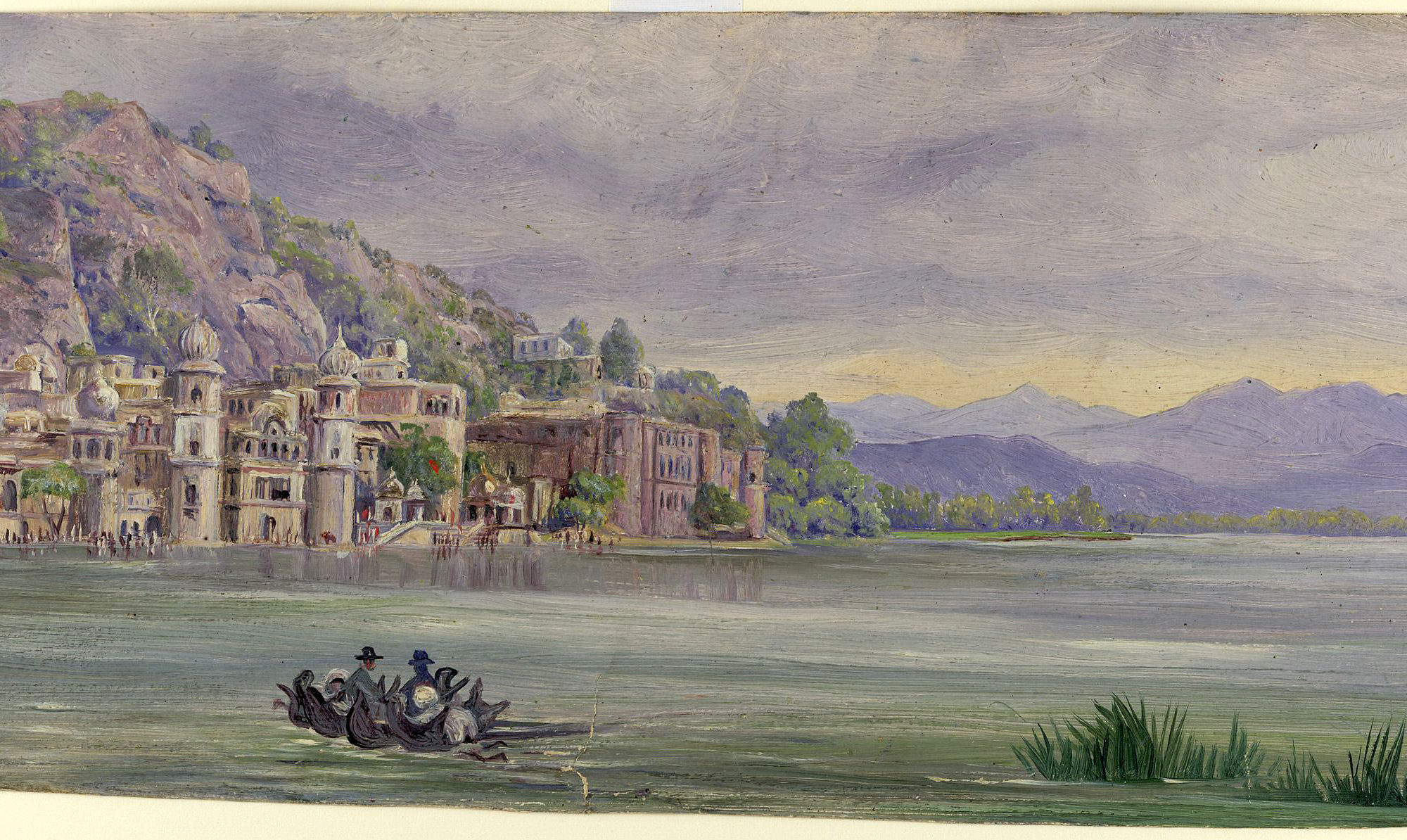

Originating in ‘cratons’ – ancient, tectonically stable landscapes – the north-flowing cratonic rivers like Chambal, Betwa, Ken, and Son are characterised by deeply-carved, steep-walled valleys. Craton rivers are rain-fed, flow through semi-arid, convex zones and an absence of engineering structures (so far) allows them to carry rich sediment and create fertile zones along the river stretch, as they have for millennia. The government’s recent Ken-Betwa river-linking scheme will threaten this process, with the heavy river flows having serious impact on the tiger reserves and national parks downstream.

With the Deccan plateau dipping from west to east, most of India’s peninsular rivers run eastward into the Bay of Bengal. The east-flowing peninsular rivers include Godavari, Krishna and Cauvery. These rivers originate in the elevated, high-rainfall Western Ghats escarpments, flow through well-carved channels, occasionally forming waterfalls where there is a sudden change in terrain. Just before reaching the plains, they spread out into large deltas and creating important mangrove and littoral habitats that sustain coastal fisheries.

Photo: public domain

Counter-intuitive to the eastward slope of the peninsula, the west-flowing peninsular rivers, Narmada and Tapi, travel towards the Arabian Sea – flowing through (still tectonically active) rift valleys. The hard bedrock results in a single channel with few meanders, and intense velocities during floods. Staggering formations of alluvial or marble cliffs, steep gorges, and eddying rapids define these riverscapes today.

Photo credit: Aksveer (CC BY-SA)

Running along the 10-25 kilometre-wide margin of the Western Ghats escarpment, coastal escarpment rivers are short, run through gorges or well-carved basins, and form spectacular waterfalls. Coastal rivers are fuelled by orographic rainfall – caused by clouds encountering a mountain barrier, where the run-off causes intense erosion along the basaltic Western Ghat slopes.

In conclusion, this classification by behaviour and appearance of India’s rivers provides clues to the past and the present-day water regimes, erosion rates, and sediment transport. From an economic standpoint (not within the purview of the paper), these clues can help us understand the hydropower potential of a river, the maintenance costs involved, and agricultural viability of the adjacent land. It can help us think of rivers not as isolated bodies, but as a part of a broader landscape – a riverscape, if you will – whose persistence and memory can inform and improve our future.

Rivers of Memory: India by Devayani Khare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.