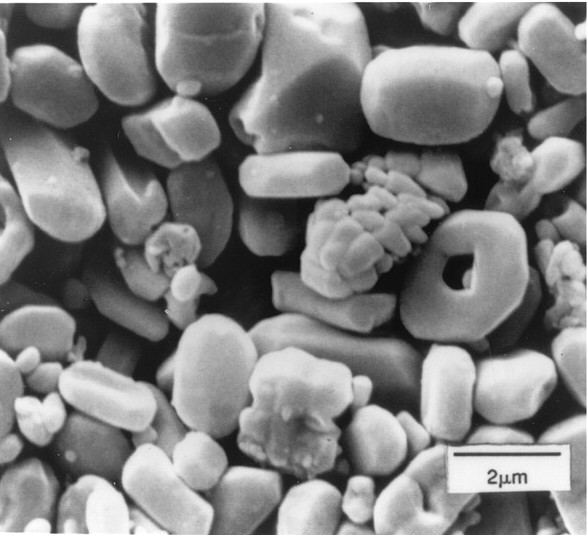

Featured image: Crystals of the mineral barite from the deep ocean (Adapted from Kastner (1999)). These crystals precipitated in ocean sediments and are about 9 million years old, similar in age to some of the barite samples from the study discussed here.

Paper: A 35-million-year record of seawater stable Sr isotopes reveals a fluctuating global carbon cycle

Authors: Adina Paytan, Elizabeth M. Griffith, Anton Eisenhauer, Mathis P. Hain, Klaus Wallmann, Andrew Ridgwell

What do ancient ocean sediments and the walls around x-ray machines have in common? One possible answer? Sometimes the mineral barite is an important part of both! Barite (or barium sulfate) is able to block gamma and x-ray emissions, and therefore is sometimes used in high-density concrete in hospitals and laboratories. In the deep ocean, tiny crystals of barite naturally accumulate on the seafloor over time, particularly in regions ideal for this mineral formation where many decaying remains of organisms sink to the seafloor. The chemistry of this barite can give scientists clues into Earth’s past, which is what Adina Paytan and her colleagues did in this study.

Continue reading “Buried treasure in the oceans: chemistry of small deep-sea crystals hints at past carbon cycling”