Thawing permafrost is known to be a substantial source of greenhouse gases to our atmosphere, yet scientists may still be underestimating this frozen giant. Permafrost soils store twice the amount of carbon than is currently in the atmosphere, but icy temperatures prevent microbes from converting carbon in the soil to greenhouse gasses. This creates a sort of carbon lockbox in the arctic. However, as climate change warms our planet, this once-frozen carbon threatens to escape to the atmosphere as the potent greenhouse gas, methane. A new study by Dr. Katey Walter Anthony and colleagues changes the paradigm of permafrost science and warns that current models underestimate the amount of methane that permafrost thaw in regions of Alaska and Siberia could release.

Continue reading “Permafrost Paradigm Shift Suggests More Methane Emissions to Come”Methanotrophs: Nature’s catalytic converters

Featured image: A car exhaust pipe, by Matt Boitor on Unsplash.

Paper: Microbial methane oxidation efficiency and robustness during lake overturn

Authors: M. Zimmerman, M. Mayr, H. Bürgmann, W. Eugster, T. Steinsberger, B. Wehrli, A. Brand, D. Bouffard

If you own a car, you’re likely aware that your engine emits greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Although we usually think of cars and other human activities as the primary source of such greenhouse gases, living ecosystems can also produce these gases through natural processes. For example, lakes are an important global source of methane, a potent greenhouse gas produced in lake sediments as organic matter decomposes. In their recent paper, Zimmerman and colleagues focus on a small but mighty team of microbes that work hard to limit the amount of methane emitted from lakes.

Continue reading “Methanotrophs: Nature’s catalytic converters”How to connect methane in atmosphere to a planets geology and biology

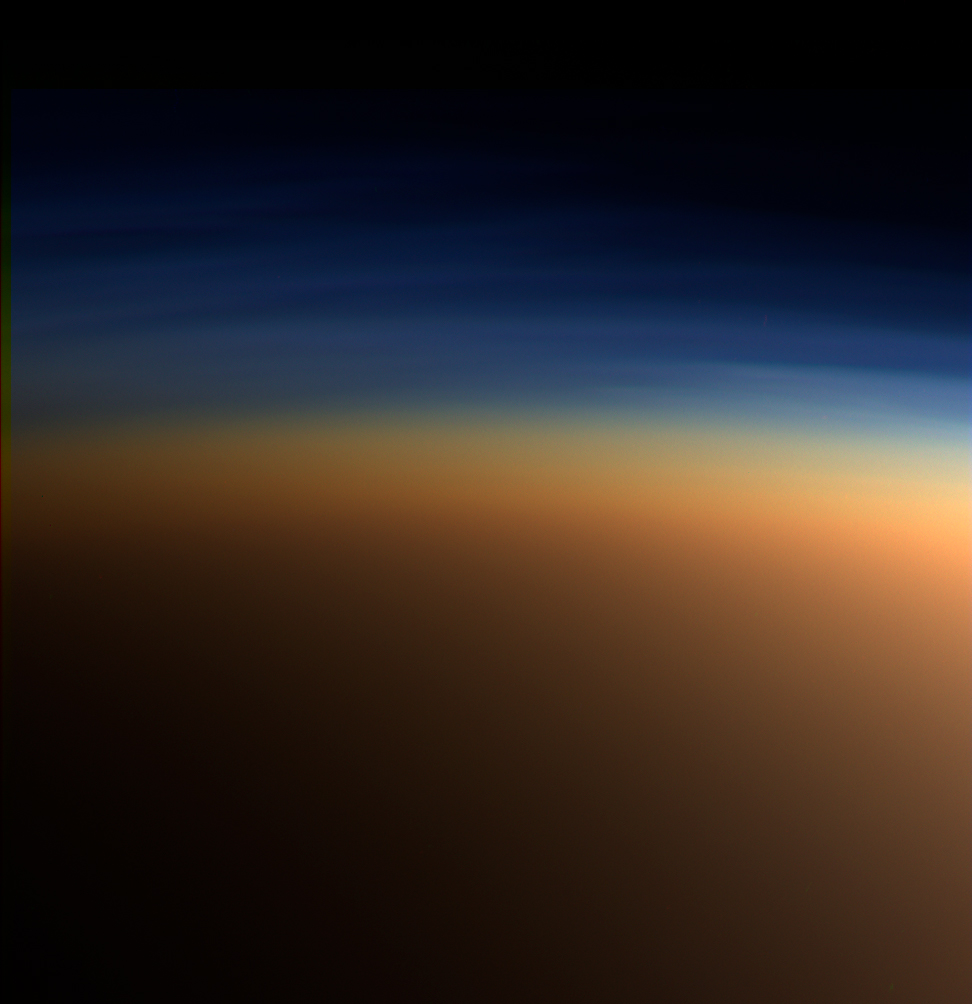

Featuring image: Titan’s atmosphere is rich in organic molecules, but we still don’t know if there is life on Saturn’s icy moon. With JWST and the coming generation of telescopes, we will be able to observe the atmospheres of exoplanets. Is there a way to search for life on these distant worlds? NASA/JPL, public domain (CC0).

Paper: The case and context for atmospheric methane as an exoplanet biosignature

Authors: M. A. Thompson, J. Krissansen-Totton, N. Wogan, M. Telus and J. J. Fortney

Visiting and exploring exoplanets for extraterrestrial life still belong to the realm of science fiction. However, the coming generation of telescopes will enable us to look into the atmospheres of exoplanets and search for possible biosignatures, chemical compounds that could indicate the presence of life.

Searching for life on a planet is not a trivial task. Since the first Mars landing in 1976, scientists still search for recent or ancient traces of life. It becomes even more difficult on planets that we cannot directly visit. The next telescope generation will enable us to observe the atmosphere of distant planets remotely. Are there ways to find evidence of life in a planet’s atmosphere? A new study suggests that the freshly launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could help us to search for life on other worlds.

Continue reading “How to connect methane in atmosphere to a planets geology and biology”Breaking: all living things may produce methane, including you

Featured Image: Collage of Life. Image courtesy Bryan K. Lynn.

Paper: Methane formation driven by reactive oxygen species across all living organisms

Authors: Leonard Ernst, Benedikt Steinfeld, Uladzimir Barayeu, Thomas Klintzsch, Markus Kurth, Dirk Grimm, Tobias P. Dick, Johannes G. Rebelein, Ilka B. Bischofs, Frank Keppler

You may have heard how methane is a “potent greenhouse gas.” But what does that mean? Even though there are fewer molecules released in our atmosphere when compared to carbon dioxide, methane holds onto heat 25 times more effectively than carbon dioxide. In other words, if carbon dioxide acts as a linen sheet around Earth, then methane is akin to a downy comforter.

Continue reading “Breaking: all living things may produce methane, including you”Mysterious methane on Mars

Featuring image: northern rim of Gale Crater viewed by Curiosity. NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS, public domain (CC0)

Paper: Day-night differences in Mars methane suggest nighttime containment at Gale crater

Authors: C. R. Webster, P. R. Mahaffy, J. Pla-Garcia, S. C. R. Rafkin, J. E. Moores, S. K. Atreya, G. J. Flesch, C. A. Malespin, S. M. Teinturier, H. Kalucha, C. L. Smith, D. Viúdez-Moreiras and A. R. Vasavada

Methane is a gas often connected to life on Earth. NASA’s Mars rover reported the detection of methane, but discrepancies with other missions puzzled researchers. Is there methane on Mars or not? A new study tries to answer this question in a windy way.

Methane is a possible biosignature for extraterrestrial life and therefore, one of the goals of the Mars rover Curiosity was to search for methane. Curiosity was able to detect varying amounts of this gas over the years, but the existence of methane in the Martian atmosphere could not be confirmed by analysis from satellites. Now, Christopher Webster and his group were able to explain the variations as well as the discrepancy between ground-based and satellite analysis by developing a detailed model of the wind systems at Gale crater.

Rust to the Rescue?

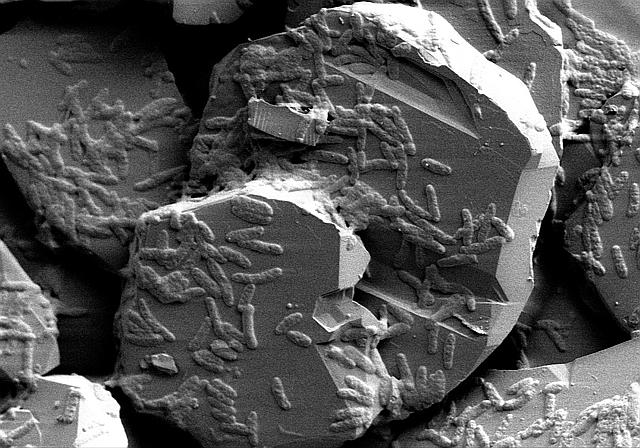

Featured Image: Shewanella putrefaciens CN-32 (a microbe capable of eating iron) on hematite (a rock containing iron). Image courtesy Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL). Used with permission.

Paper: Organic matter mineralization in modern and ancient ferruginous sediments

Authors: André Friese, Kohen Bauer, Clemens Glombitza, Luis Ordoñez, Daniel Ariztegui Verena B. Heuer, Aurèle Vuillemin, Cynthia Henny, Sulung Nomosatryo, Rachel Simister Dirk Wagner, Satria Bijaksana, Hendrik Vogel, Martin Melles, James M. Russell, Sean A. Crowe, Jens Kallmeyer

Just as a crow may use a rock to crack a nut, certain microbes can use solid iron to crack open methane. This consumption limits the amount of methane lost from lakes into the atmosphere, making it a crucial process in mitigating production of greenhouse gasses. These microbes are abundant in freshwater sediments, and their specialized mechanism for cracking open methane is most likely one of the oldest metabolisms on Earth, providing a modern-day window into the past.

Continue reading “Rust to the Rescue?”Isotopes Begin to Unlock the Mystery of Methane Source in the Scheldt Estuary

Featured Image: Eastern Scheldt Estuary near Zeeland, Netherlands. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons/ Luka Peternel, CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Paper: Carbon and Hydrogen Isotope Signatures of Dissolved Methane in the Scheldt Estuary

Authors: Caroline Jacques, Thanos Gkritzalis, Jean-Louis Tison, Thomas Hartley, Carina van der Veen, Thomas Röckmann, Jack J. Middelburg, André Cattrijsse, Matthias Egger, Frank Dehairs & Célia J. Sapart

Estuaries are dynamic coastal environments where freshwater and saltwater collide and mix. Across the world, estuaries regularly have higher methane concentrations in the water than would be expected from equilibrium with the atmosphere. If the water was in equilibrium, or at a happy balance, with the atmosphere, then there would be no net transfer of methane to the atmosphere. Because there is more methane than expected in the water, estuaries are a source of this potent greenhouse gas, methane (CH4), to the atmosphere. The problem is that the processes leading to the excess methane in the estuary’s surface water are not well known in many European estuaries.

Continue reading “Isotopes Begin to Unlock the Mystery of Methane Source in the Scheldt Estuary”Unexpected consequence of permafrost thaw: potentially less methane released into the atmosphere

Authors: Clarice R. Perryman, Carmody K. McCalley, Avni Malhotra, M. Florencia Fahnestock, Natalie N. Kashi, Julia G. Bryce, Reiner Giesler, Ruth K. Varner

Permafrost is a blanket of soil that is frozen for more than two years and can trap its contents for hundreds to thousands of years. Now that permafrost soil is thawing. This is particularly significant in peatland permafrost because these wetlands sequester high amounts of carbon. As peatland permafrost degrades, methane emissions are expected to increase as the water table rises and provides a suitable environment for methane production by microbes.

Continue reading “Unexpected consequence of permafrost thaw: potentially less methane released into the atmosphere”