Feature image: Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India by Nireekshit, CC BY-SA 3.0

Article: Archaeoseismological potential of the Indian subcontinent.

Authors: Miklós Kázmér, Ashit Baran Roy and Siddharth Prizomwala

India’s ancient monuments whisper more than just stories of past empires and civilizations: they also tell tales of its geological past. Evidence of earthquakes is etched in stone, displacements and warps that can help us identify past seismic events.

India’s documentation of earthquakes is sketchy, pieced together from historical data, monographs, and British records. In 1898, the first seismograph was established in Pune, Maharashtra, but serious instrumental recording only began when the 1967 Koyna Dam earthquake struck.Such a short record is not enough to map out active seismic regions or understand recurring earthquakes, so some scientists are turning to archaeological evidence.

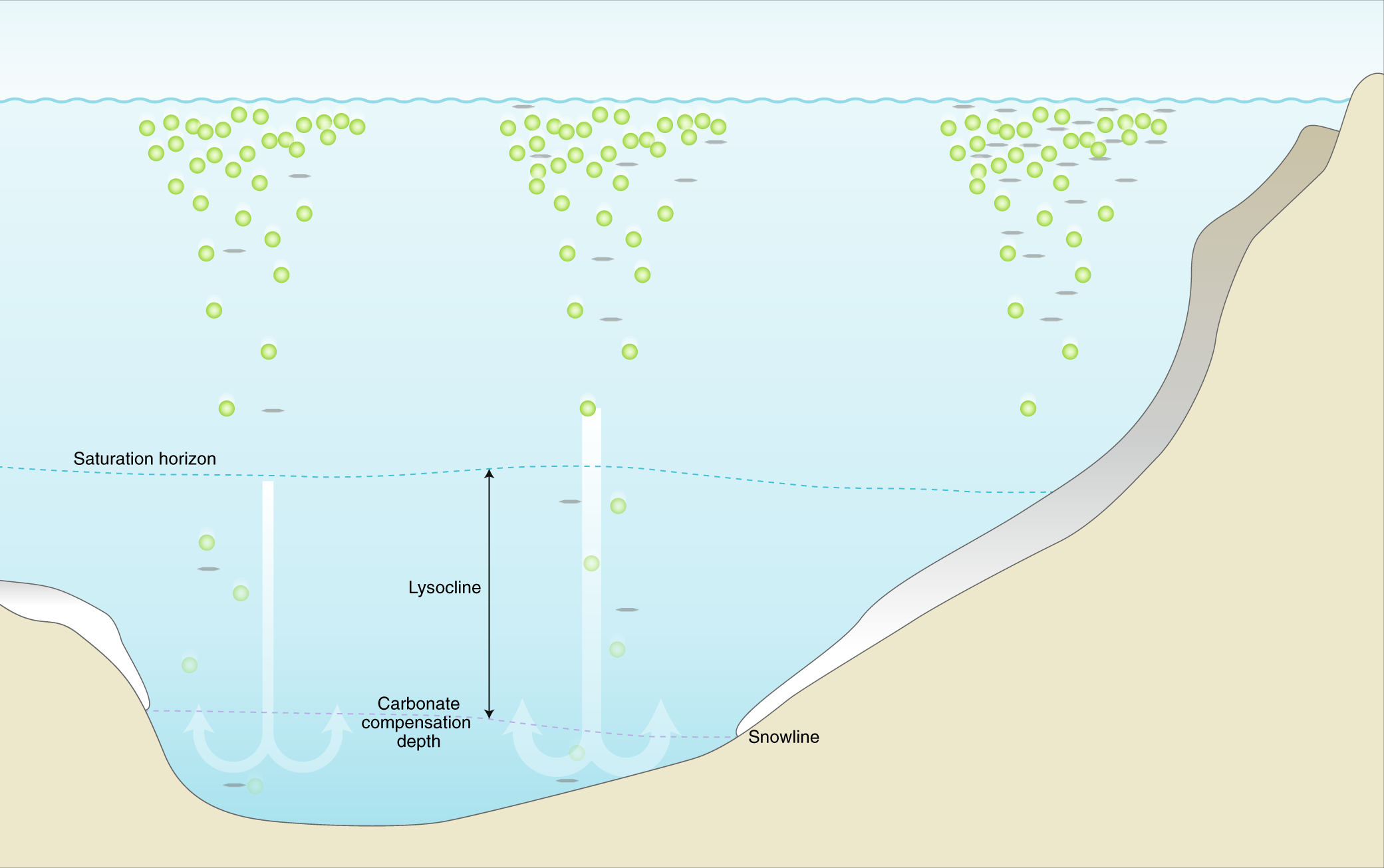

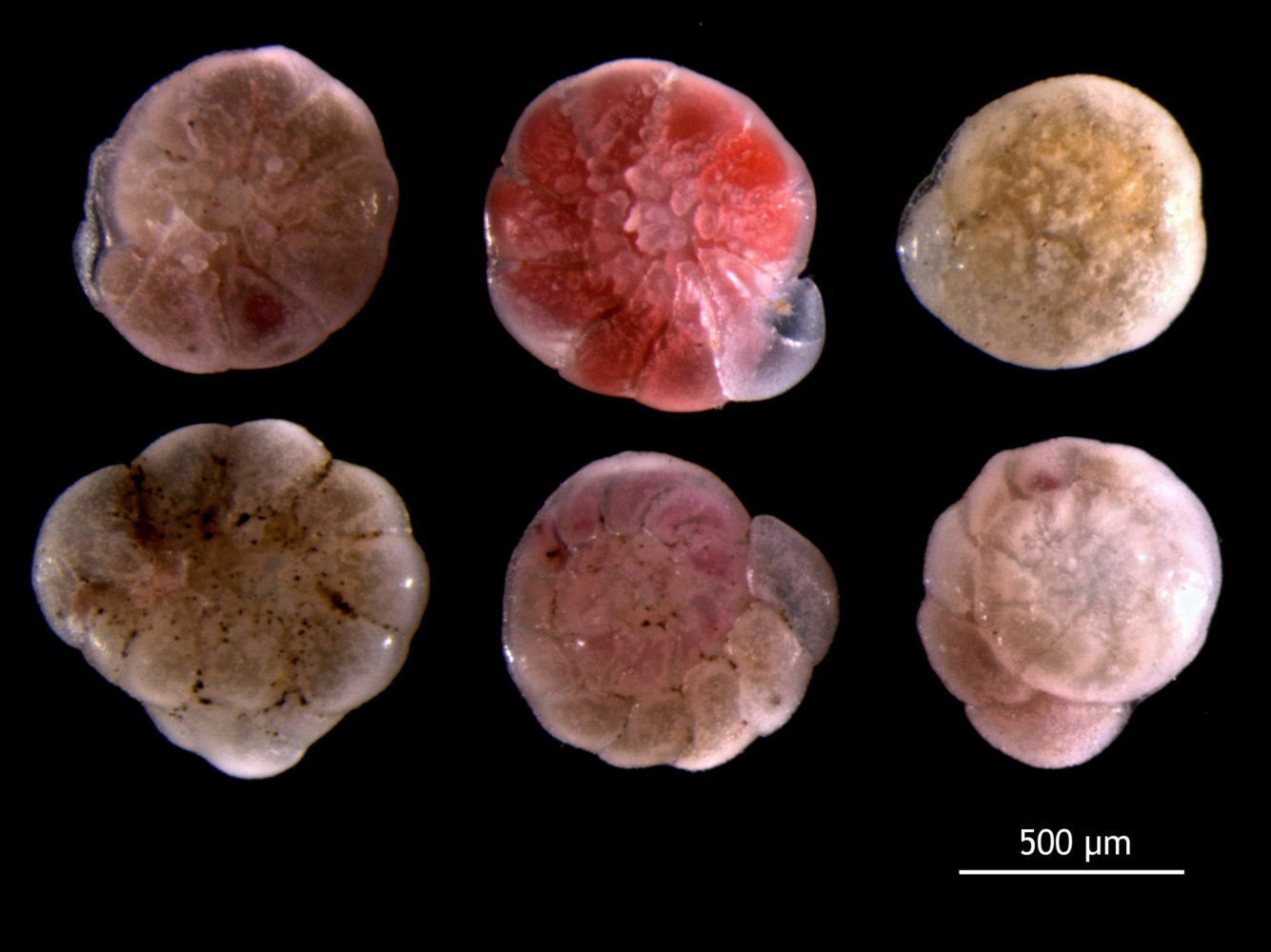

Archaeoseismology studies past earthquakes by analysing damage to archaeological sites. How much damage an earthquake does to a structure depends on how hard or soft the ground beneath is, and damage may be mitigated through preventative building techniques. Earthquakes can result in shifts and tilts in masonry or brickwork, displaced walls, warped floors, missing sections, and sometimes, a complete collapse of the structure. The Earthquake Archaeological Effects (EAE) scale helps categorise the intensity of past earthquakes based on observations of structural damage.

A recent paper by Kazmer et al., looks at earthquake damage to 3 late medieval UNESCO World Heritage sites: Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu (7th-8th CE), the Qutub Minar complex in Delhi (12th-19th CE), and Konark near Bhubaneshwar in Odisha state (13th CE). All three sites feature masonry buildings commonly seen in 7th and 12th centuries CE architecture across the Indian subcontinent. The seismic history of the subcontinent is understudied compared to the seismically active Himalayan terrain.

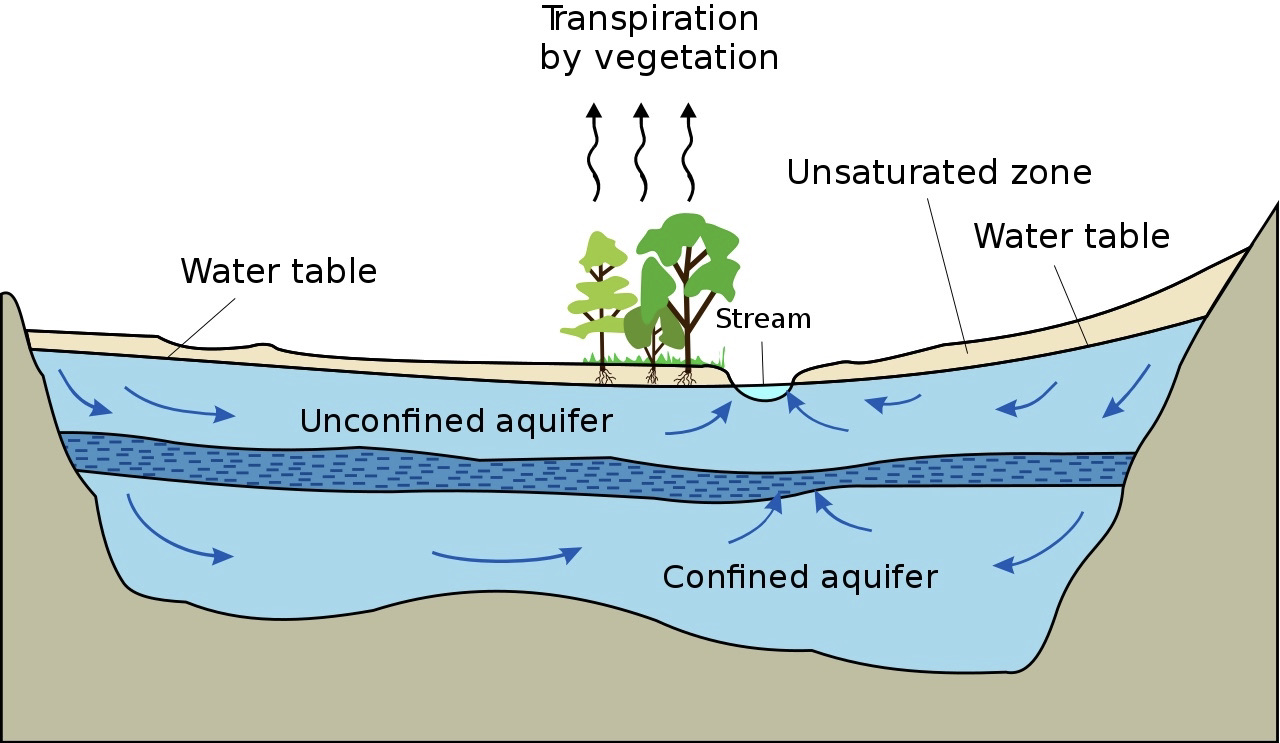

The tilt of masonry wall and floor at the Shore Temple in Mahabalipuram indicates liquefaction, a sudden loss of soil stability that can be caused by a seismic shock.. In the Qutub Minar complex, damage to the minar including masonry blocks at the top of Iltutmish’s tomb with gaps of about 5 cms are attributed to an earthquake in 1803. At Konark, smaller temples around the Sun Temple display shifted blocks. Other temples are missing a shikhara or deul, the temple spire or tower, which might have been toppled by an earthquake.

Beyond categorising such damage, archaeoseismology can indicate the date or date interval, location, and intensity for both seismically active and less active regions. Comparisons with historical records can offer broader insights into the Indian subcontinent. The volcanic plateau that forms the Indian peninsula has long been considered a ‘stable’ region, yet all 3 sites in this study located on the ‘Indian shield’ indicate otherwise – the region has seen earthquake activity in the past.

Over the years, monuments have undergone intensive restoration by various rulers, British colonial authorities and the Archaeological Survey of India to preserve them for future generations, but in the process, the evidence of past earthquakes has been erased. Kazmer and co-authors suggest that archaeoseismic studies are conducted before all large-scale restoration projects. That way, we can ensure both the historical and geological legacies are preserved for posterity.

Etched in stone: tracing earthquakes through archaeological ruins by Devayani Khare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.