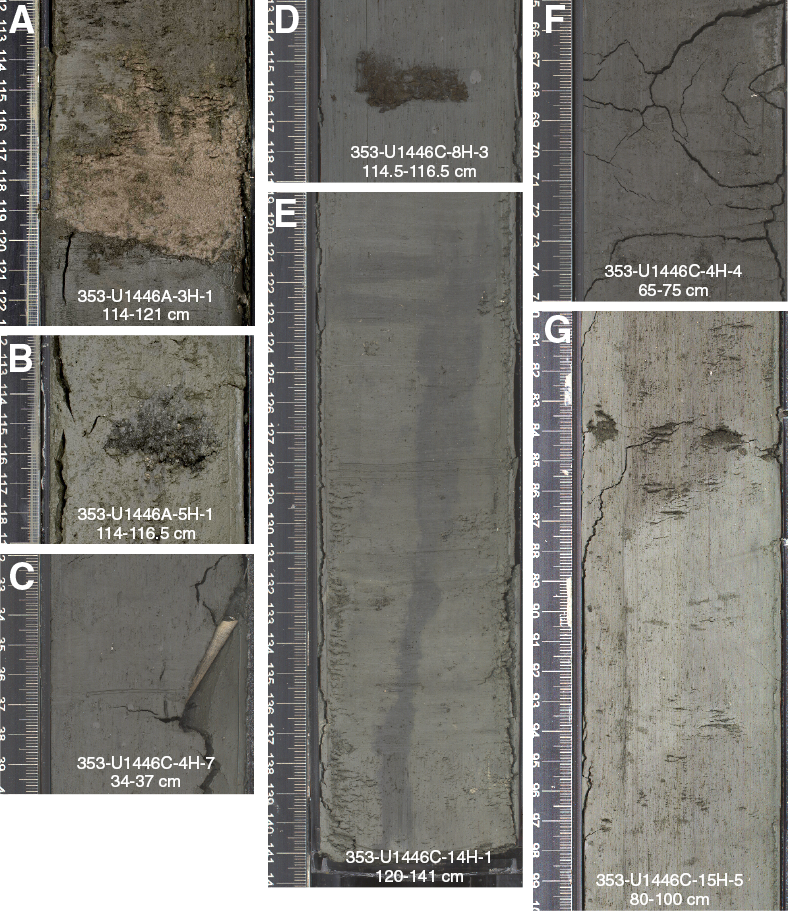

Featured Image: Line-scan image of sediment core from the Bay of Bengal. Image from the International Ocean Discovery Program. A. Volcanic ash associated with the Toba eruption. B. Pyrite-, foraminifer-, and shell fragment–rich sandy patch in foraminifer-rich clay with biosilica. C. Scaphopod in nannofossil-rich clay with foraminifers. D. Wood fragments in clay. E. Large dark gray burrow filled with the overlying sediment. F. Core disturbance (cracks) due to gas release when core liner was drilled on the catwalk. G. Minor core disturbance due to mud and water flow-in along the edges of the liner (~1 cm thickness).

Paper: Increased interglacial atmospheric CO2 levels followed the mid-Pleistocene Transition

Authors: Masanobu Yamamoto, Steven C. Clemens, Osamu Seki, Yuko Tsuchiya, Yongsong Huang, Ryouta O’ishi, Ayako Abe-Ouchi

Mention of the ice age may conjure up images of giant mastodons, ferocious saber-tooth tigers, or of a prehistoric squirrel trying so desperately to secure his acorn—all taking place on the vast amount of ice that covered portions of the globe. We know that periods of ice cover followed by stretches of warm weather was a standard pattern in our Earth’s history*, but there was something special about the last ice age (during the Pleistocene) and how long it hung around.

Continue reading “Greenhouse gasses, ice cover, and the deep ocean shape Earth’s paleoclimate in unexpected ways”