Paper: Modeling Groundwater Inflow to the New Crater Lake at K¯ılauea Volcano, Hawai’i

Authors: SE Ingebritsen, AF Flinders, JP Kauahikaua, and PA Hsieh

Accompaniment to the Third Pod from the Sun episode

When we think of opposing forces in the natural world, fire and water come quickly to mind; elemental powers always at odds, one winning out over the other. There are a few interesting times and places, though, where they can co-exist, occupying some of the same spaces in the landscape. Perhaps the most visible example of these in the geological world are hydrothermal systems in volcanically active regions, places where earth’s internal heat meets subterranean water with, at times, explosive results.

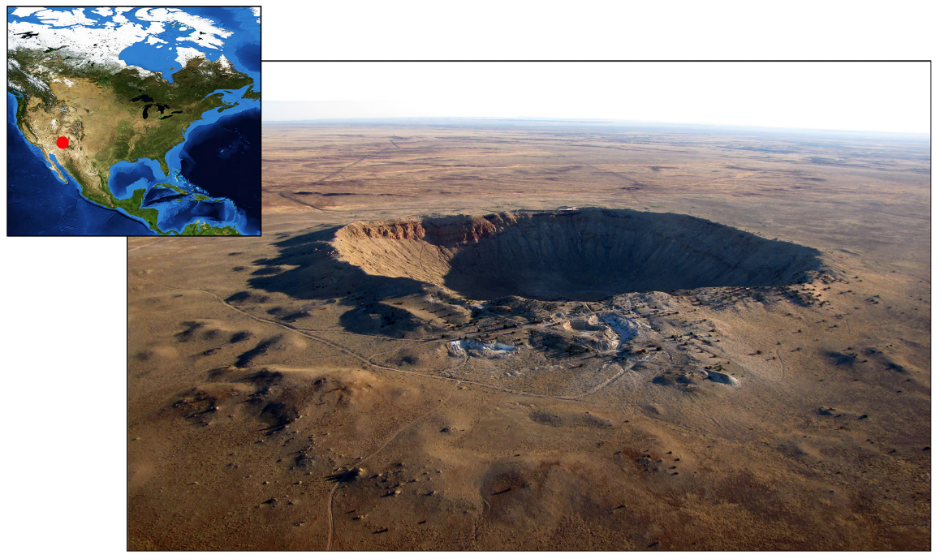

For decades the crater at the summit of the Kilauea volcano in Hawai’i, one of the world’s most active volcanoes, was filled with a pool of lava. The constant flow of magma churning up from the volcano’s depths kept this lava lake supplied with fresh molten material.

That is, until a major eruption in 2018 shifted the volcanic pipelines beneath the lake causing it to empty dramatically at the same time major fissure eruptions were sending waves of lava over residential areas near the eastern flank of the mountain. When a now-empty summit crater began to fill with water, no one was quite sure what to expect.

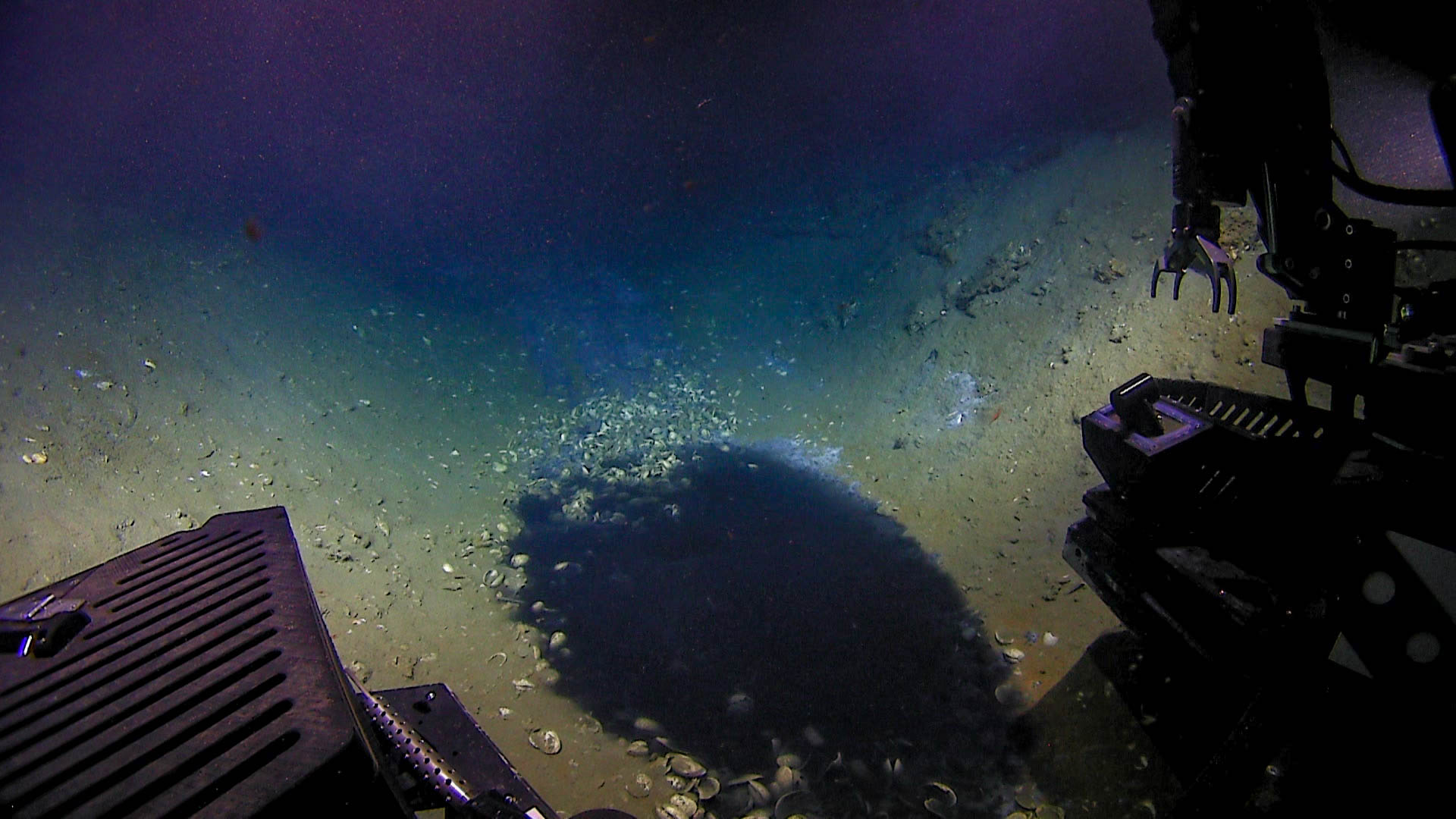

Eruptions at Kilauea have been frequent occurrences over the last at least 200 years with varying frequency and intensity. Some of these events have led to what geologists call ‘phreatic eruptions’, highly explosive events that occur when erupting lava comes in contact with cold water causing a high energy eruption of steam, ash, and rock fragments. Often in Hawai’i this occurs when lava flows reach the ocean; however, in the 2018 eruption, groundwater posed a new concern. When the lava lake at the summit began to drop below the water table, both water and lava were essentially trying to fill in the same spaces. At that point there was speculation that some highly explosive events could be imminent as the lava reached the groundwater table and larger volumes of water began to flow into the crater. Relatively little was known about the groundwater table in the area and how long it would take to fill the now empty lakebed emptied of lava.

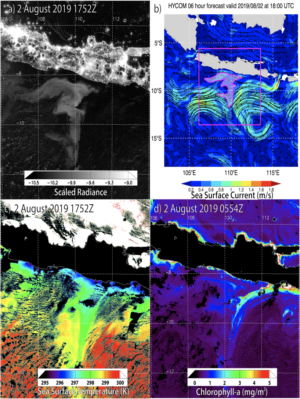

Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) hurried to develop new conceptual and numerical computer models to predict how the balance between lava flow and groundwater flow would shift as these internal conduits in the mountain emptied of molten material and began to fill with water. The groundwater flow models were challenged by the temperatures and pressures involved in the Kilauea scenario and initial predictions ranging from 3 to 24 months were narrowed as the lake began to fill in July of 2019, about 14 months after the lava lake collapse. In a paper in the journal Groundwater they explain how water flow was delayed by many months by the inability of groundwater to move through the extremely hot rock. New observations of on the ground conditions, such as inflow, temperature, and evaporation rates helped to refine the existing model to better understand the potential for future interactions in the crater and give volcano observers better tools to predict these potentially hazardous magma-water interactions in future eruptions.

Water under Fire by Avery Shinneman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.