Featured Image: Scientist Ceth Parker moving through a passageway within an iron formation cave. Photo courtesy of the University of Akron.

Authors: Ceth W. Parker, John M. Senko, Augusto S. Auler, Ira D. Sasowsky, Frederik Schulz, Tanja Woyke, Hazel A. Barton

Consider this: microscopic creatures literally moving tons of rock before your very eyes. It seems too fantastical, but maybe not if you’re in the Brazilian tropics. In new work, scientists have detailed these stealthy and microscopic processes, naming a new cave generation pathway called exothenic biospeleogenesis, or “behind-wall life-created” caves.

Most caves in this tropical region are formed by water flowing underground and dissolving molecules in the rock, compromising their stability and leading to erosion. However, some rock formations contain iron molecules that are insoluble, meaning they can’t be dissolved in water… yet these caves are still forming. Enter iron-eating microbes! These microscopic munchers can eat the insoluble iron molecules, converting them into a water-soluble molecule which is then washed away by running water. But there’s a catch: these microbes are unable to eat iron in the presence of oxygen, so they can’t exactly sit atop a rock in the open air, or even continue eating the iron when the erosion begins and introduces oxygen underground. Somehow, these caves keep forming, but how?

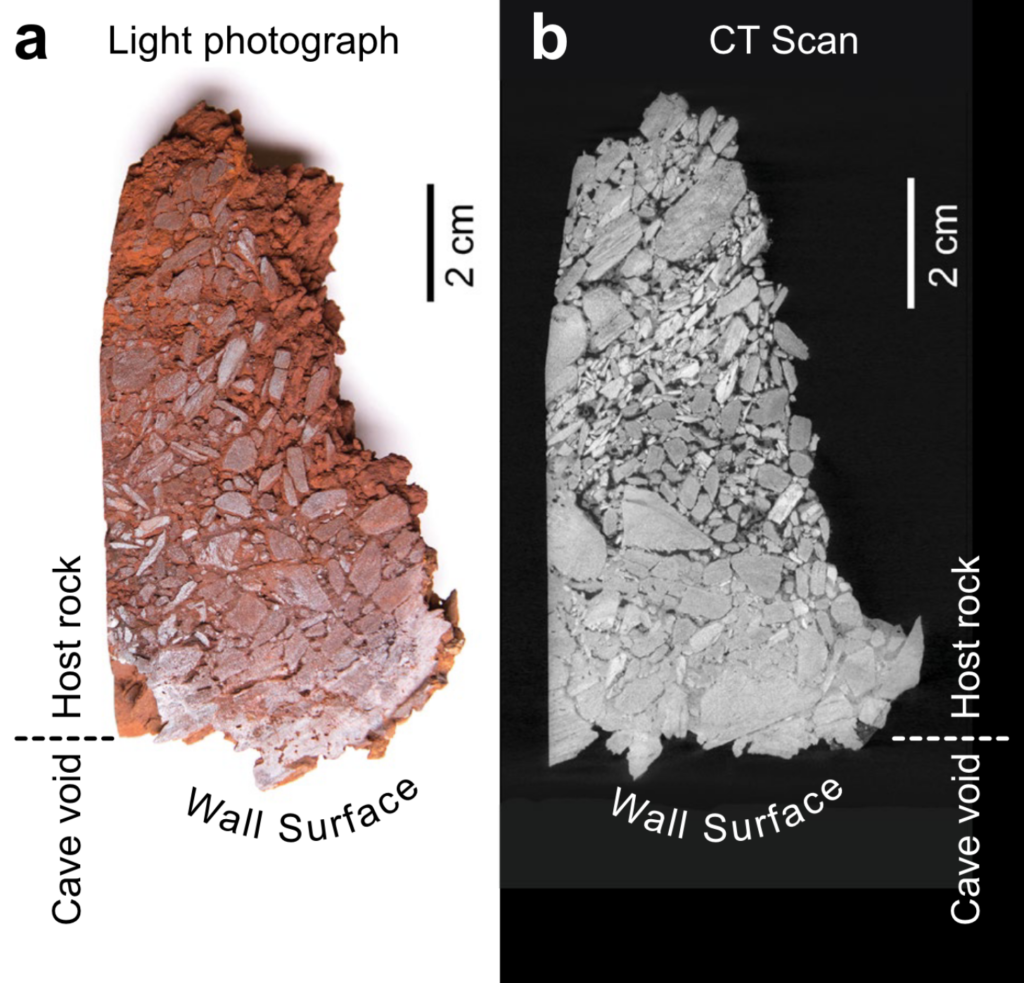

In a new study, Parker and colleagues went spelunking into these small, oblong caves and began tapping on and drilling into the seemingly solid walls. Yet, they found that only a fraction of an inch beyond the hard cave wall was a porous, fragmented space (Image). The hard-outer wall will eventually give way as these pores expand, crumbling into the cave and exposing the new walls to oxygen. However, the cells just beyond the wall are protected and continue to eat through the iron-rich wall. In addition to oxygen, water availability in these caves limit the microbial meals. Seasonal cycles of rain and water flow gain the microbes access to the insoluble iron by washing away bits of microscopic debris, leading to larger and larger pore space as seasons pass.

Once Parker and colleagues identified this process, they tested their hypothesis by inserting iron-rich rectangles of metal (called coupons) into the cave wall. They came back a year later and imaged the coupons using a high-powered microscope and found microbial feeding tracks, or porous grooves left behind as a microbe eats away the iron. Using the depths of the feeding tacks, Parker and colleagues were able to calculate how quickly these microbes may eat away the rock, finding that a substantial cave can be formed in as little as 129,000 years. While that may feel like a long time, other caves created by water flow take millions of year to form–that’s like comparing the speed of a race car to a bicycle!

Can this happen anywhere? Not necessarily–there’s something special about these caves in the Brazilian tropics; exothenic biospeleogenesis can occur here because of 3.7 billion years old buildup of insoluble, rusty iron known as “banded iron formations“. Around these massive formations is a layer of incredibly hard rock that protects the banded iron formations form billions of years of wear-and-tear and it’s behind this layer of hard rock where these microbes form new caves.

Scientists are just beginning to explore the concept of exothenic biospeleogenesis, or cave formation by microbes eating insoluble iron and leaving caves in their wake as water washed the debris away. It’s not every day a new cave generation method is identified, rather less so than by microscopic miners!

Microscopic Miners: How invisible forces create tropical caves by Jessica Buser-Young is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.