Article: Why productive lakes are larger mercury sedimentary sinks than oligotrophic brown water lakes

Authors: Martin Schütze, Philipp Gatz, Benjamin‐Silas Gilfedder, Harald Biester

Advisories and outreach campaigns have worked for years to help us understand how the fish we eat impacts the amount of hazardous mercury we consume. Mercury is present in the environment naturally in several forms, but consumption advisories warn against methyl-mercury. This substance not only moves throughout the aquatic ecosystem, but bio-accumulates, or increases in concentration, as it moves higher in the food chain. But the size of the fish is not the only influence on its mercury levels – it may also matter where it lives.

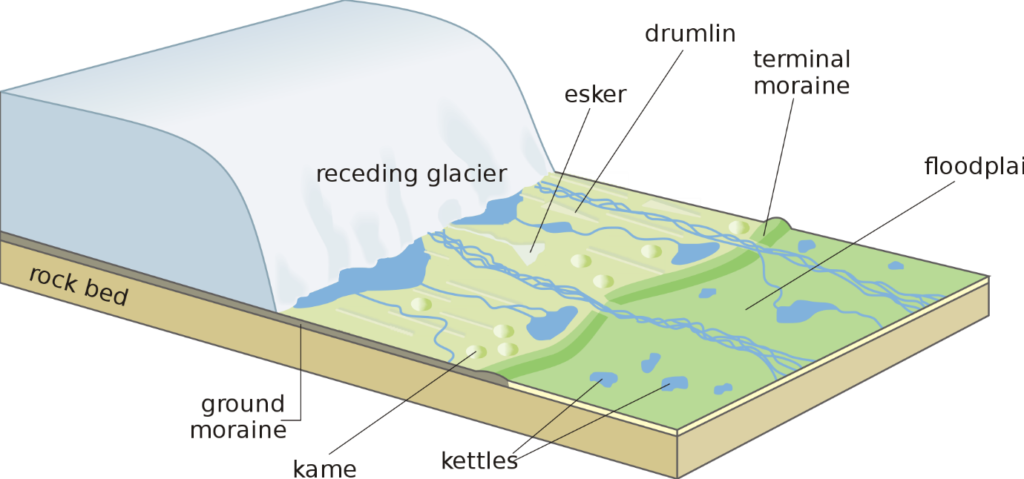

Most mercury in lakes is initially deposited from the atmosphere. These levels vary regionally, influenced by things like weather patterns and local industry. Mercury is also deposited on land, though, and it can eventually leach and erode from soils, moving through surface and groundwater into local lakes. Researchers have known for some time that the vegetation and soil types in the watershed can influence mercury influx to lakes; for example, coniferous trees generally take up more mercury from the atmosphere than deciduous trees, making the forest litter and, eventually, the organic rich layers of forest soils more concentrated in mercury in coniferous forests.

A recent German study compared mercury levels in two sets of lakes, looking at everything from surrounding vegetation and topography to local weather patterns, and found that previously observed findings held up; mercury levels were higher in leaf litter and organic soils than other surrounding sediments, and higher in areas with more coniferous vegetation. However, when the authors undertook mathematical modelling to balance the input of mercury from atmospheric deposition and local erosion to the outflow, the numbers didn’t add up the same way in all the lakes.

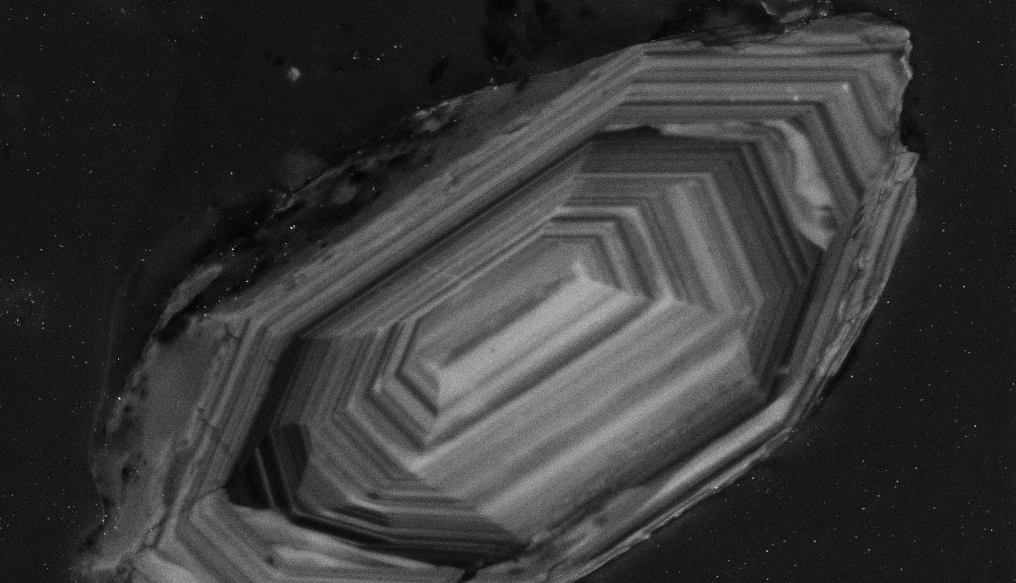

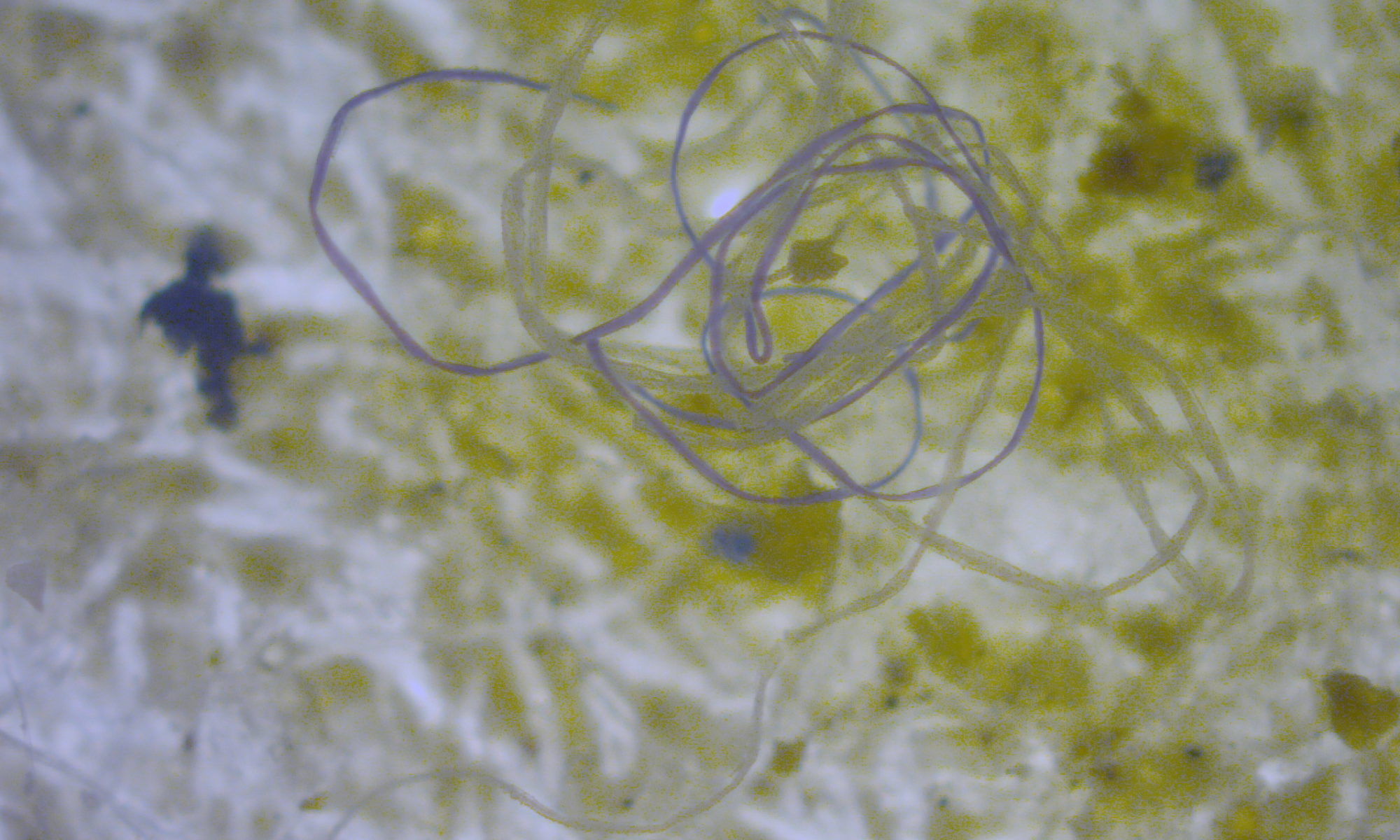

The difference, they documented, was in the productivity of the lakes. Algae scavenge mercury from the water column and, when they die and sink, take the mercury along. This leads to mercury deposition in the lake sediments. By comparing measurements of mercury in the water column, in accumulated sediments on the lake floors, and in sediment ‘traps’ that collect sediment as it is falling through the water column, the researchers showed that large algal blooms significantly increase the transport of mercury from the water column into lake sediments. In a set of forested, alpine lakes that were low in nutrients and had few algal blooms, the monitoring data showed that most of the mercury inputs were eventually lost to a combination of river outflow, re-emission to the atmosphere, and sediment burial. In lakes with higher nutrient loads and more common algal blooms, a similar input of mercury was translated into a much higher flux to the lake sediments, which they traced to the concentration of mercury in the algal organic matter.

The high rate of mercury delivery to lake sediments, especially in very productive lakes, may be bad news for fishing. The high rate of organic matter input to the sediment also leads to a low-oxygen environment which can spur the bacterially-mediated chemical process that turns mercury into the methyl-mercury form. When it is released and recycled from the sediments, it works its way up the food chain. Lakes in many parts of the world are seeing increased algal growth from warmer temperatures and higher nutrient input, and the resultant highly-visible algal blooms may have a significant impact on the invisible movement of hazardous mercury to consumers at the top.

You are what you eat…and also where you fish by Avery Shinneman is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.