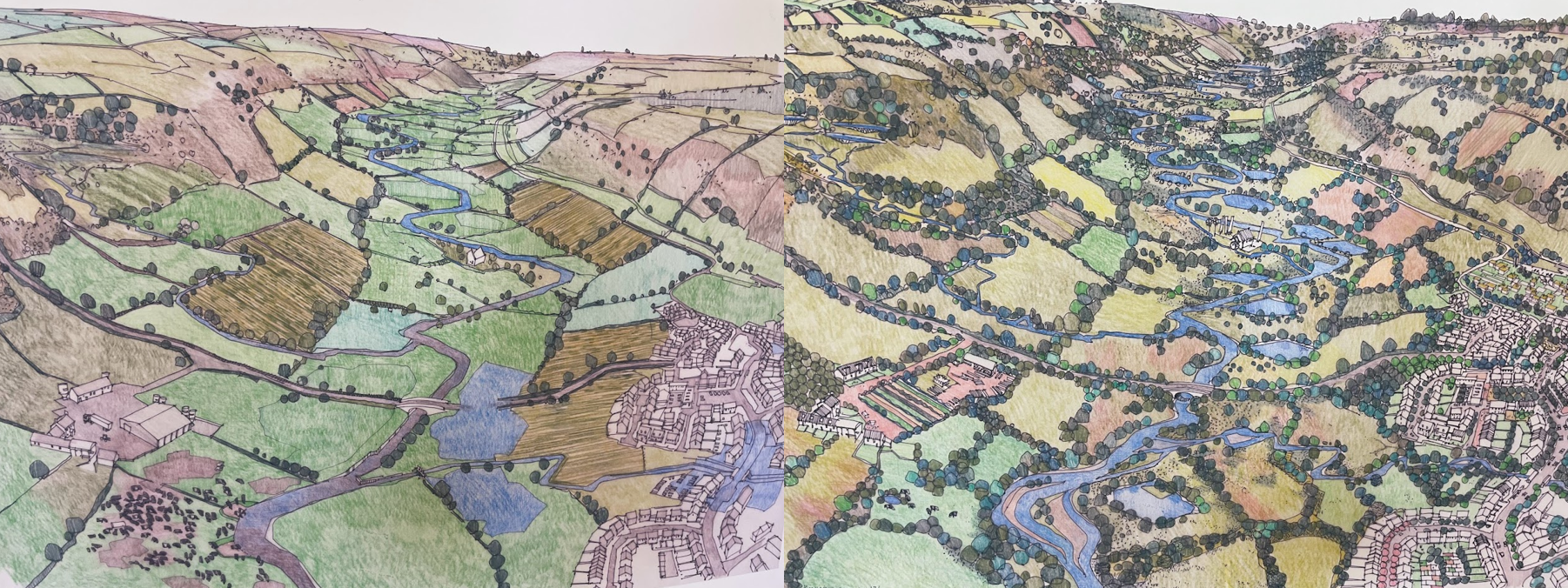

Featured Image: Two striking illustrations of the river Culm catchment in the UK. Created by local artist Richard Carman, the left image shows the existing (degraded) situation, while the right image depicts a co-created nature-based solutions scenario developed in collaboration with local stakeholders, including farmers and landowners, as part of the Co-Adapt project. These illustrations provide a clear visual representation of how nature-based solutions can be used to address environmental challenges in the area.

Papers: Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security; Climate-smart Soils; IPCC (2014) Report on Mitigation of Climate Change; Synthesizing US River Restoration Efforts; Limited potential of no-till agriculture for climate change mitigation; Sequestering carbon in soils of agro-ecosystems; Crop Residue Removal Impacts on Soil Productivity and Environmental Quality; Towards an EU research and innovation policy agenda for nature-based solutions & re-naturing cities.

Authors: Rattan Lal, Keith Paustian, Johannes Lehmann, Stephen Ogle, David Reay, Philip G. Robertson, Pete Smith, Humberto Blanco-Canqui and more.

Are you worried about the impact of climate change on our planet and wondering what you can do to help? Look no further than nature itself, because nature-based solutions may just hold the key to mitigating its effects through soil carbon sequestration.

Climate change is an ongoing problem that poses a significant threat to our planet. Many strategies have been proposed to mitigate climate change, including renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, and nature-based solutions (NbS). Among these, NbS have gained considerable attention because they offer a range of benefits, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions, mitigating the impact of natural disasters such as floods and droughts, and improving biodiversity.

But what are NbS, and how can they help in mitigating climate change? Nature-based solutions are interventions that work with nature to address environmental challenges. These solutions involve restoring, protecting, and managing ecosystems such as forests, wetlands, and grasslands. One of the significant benefits of NbS is soil carbon sequestration, which refers to the process of capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in soil.

Soil carbon sequestration is a powerful tool to mitigate climate change because it can store carbon for decades or even centuries. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), soil carbon sequestration can reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations by up to 15% by 2050. This approach has gained traction in Europe, where various projects have been implemented to sequester carbon in soils.

For example, in the UK, the Farm Carbon Cutting Toolkit is a non-profit organization that works with farmers to adopt practices that increase soil carbon levels. One such practice is the use of cover crops, which are planted between cash crops to prevent soil erosion, improve soil health, and increase carbon sequestration. According to the organization’s website, “the planting of cover crops, such as clover, can increase soil organic matter and carbon content by up to 15% over ten years.”

Similarly, in France, the 4 per 1000 initiative aims to increase soil carbon content by 0.4% per year. This initiative focuses on a range of NbS, such as agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and the use of biochar. According to a study published in the journal Nature, increasing soil carbon by 0.4% per year could offset around 3.5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

Soil carbon sequestration through NbS not only helps mitigate climate change but also has several co-benefits. For example, it can improve soil health, increase agricultural productivity, and reduce the risk of natural disasters such as floods and droughts. As Dr. Pauline Chivenge, a soil scientist at the University of Zimbabwe, explains:

”If we improve soil health, we can improve crop yields, and that translates into better nutrition and food security for communities”

However, it’s important to note that soil carbon sequestration alone cannot solve the climate crisis. We also need to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, promote renewable energy, involve the local community and implement other sustainable practices. Nonetheless, soil carbon sequestration is an important piece of the puzzle and should be considered as part of a comprehensive climate action plan.

In conclusion, nature-based solutions such as soil carbon sequestration offer a promising strategy for mitigating climate change while providing multiple benefits. By implementing NbS practices such as agroforestry, cover crops, and conservation agriculture, we can increase soil carbon levels, improve soil health, and enhance biodiversity. By implementing NbS practices, we can all contribute to mitigating the impacts of climate change and promoting sustainable development. Here are some ways you can get involved:

- Educate yourself: Learn about the benefits and potential of nature-based solutions in addressing environmental challenges. Read about case studies, best practices, and research on nature-based solutions.

- Advocate for nature-based solutions: Speak up about the benefits of nature-based solutions in conversations with family, friends, colleagues, and community members. Encourage local leaders to consider nature-based solutions in planning and decision-making.

- Support conservation efforts: Donate to conservation organizations or volunteer for conservation efforts in your community. Protecting natural areas can support nature-based solutions and the ecosystem services they provide.

- Plant trees and native plants: Trees and native plants play an important role in sequestering carbon, improving air and water quality, and supporting biodiversity. Planting trees and native plants in your yard or community can support nature-based solutions.

- Support sustainable agriculture: Sustainable agriculture practices, such as agroforestry and regenerative agriculture, can support nature-based solutions by promoting soil health, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration.

- Participate in citizen science: Citizen science projects can provide valuable data for understanding environmental challenges and the effectiveness of nature-based solutions. Participate in citizen science projects in your community or online

- Support green infrastructure: Green infrastructure, such as green roofs and bioswales, can support nature-based solutions by reducing stormwater runoff and improving air quality. Encourage your community to invest in green infrastructure or start from your own garden by removing paved surfaces and replacing them with greenery, make your own compost etc..

- Support policies and funding for nature-based solutions: Policy changes and funding can help support the uptake of nature-based solutions at local and national levels. Support policies and funding initiatives that promote nature-based solutions.

By taking action and supporting NbS practices, we can all make a difference in the fight against climate change. As Dr. Bedford, a climate change expert, reminds us:

”We all have a role to play in addressing the challenges of climate change, and implementing nature-based solutions is one of the most effective ways to do so.”

Nature’s Secret Weapon: How Nature-based Solutions Can Tackle Climate Change and More by Borjana Bogatinoska is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.